Embla Guðrúnar Ágústsdóttir

@emblan

images:

Eva Sigurðardóttir

@evasigurdar

@evasig__

evasigurdar.com

translation:

Gyða Guðmundsdóttir

“Can you kiss me, a bit longer?”

We lie next to each other, side by side, our bodies tangled in a bow. I tuck my left hand under my pillow in order to control it and it’s involuntary movements. My left arm frequently gets me into trouble and when I get nervous or excited it always reveals my feelings. It moves around and sometimes grabs after inappropriate things, like hair. There is nothing less sexy than spontaneously grabbing after her hair right in the middle of the action. But the woman lying beside me loves this left arm like she loves the rest of me. To her, the arm is a part of me, a part of what makes me sexy. Just like the thighs, my round butt and breasts.

My relationship with this left hand has never been good, and I sometimes refer to it as an object outside of my body. The left arm has always been hard to control and often caused me pain. Countless times I have wanted it gone and hidden it in photos because I found it ugly. In my journey to body awareness and self-love I have excluded my left arm, from the respect it desperately needs. I have found it too disabled, too annoying, to be included. Knowing a woman that loves this left arm has increasingly changed my attitude towards the arm. It has helped me to see and appreciate my body in a different way.

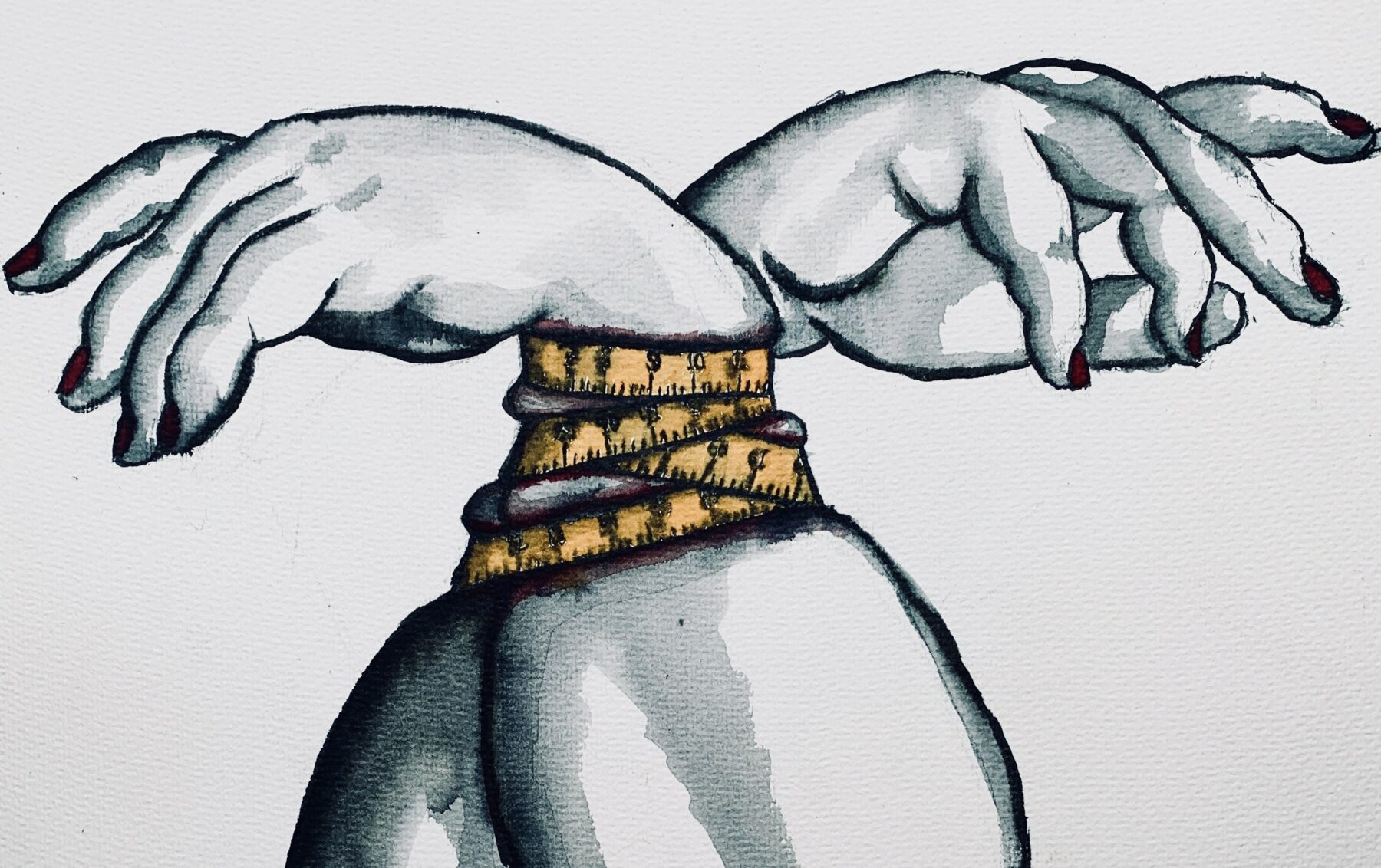

When your body does not fit into what we consider a normal body, self-love and self-respect become a radical action.

Body respect and self-love continue to gain momentum among feminists and social media campaigns that celebrate different bodies and encourage us to practice self-love. But at the same time, we have managed to market self-love as some personal goal that we all must achieve.

We say, “You must learn to love yourself in order to accept love from others”, in an attempt to empower ourselves and I am no exception there. Countless times I have said those words, to myself and others. The problem with this statement is that we create a conditioning for love which says that only some of us are worthy of love.

In a culture that constantly teaches us to hate our bodies, treat it with disrespect and long to change it, it is in fact unfair and oppressive to make the individual responsible for being worthy of love. This is precisely the way we create and maintain a culture of violence – when we set conditions for receiving love.

Alex Dacy is one of many disabled activists that takes up issues of disability, self-love and sexulaity. Dacy uses her Instagram account as platform, but it has been shut down on several occasions because the pictures she posts, of her nearly naked body, are considered inappropriate and are reported by other users as child pornography. Talking about disabled people as children and ourbodies as childlike is a tale as old as time, and we are barely considered as sexual beings. Viewing us as children, people assume that we dislike our bodies and consider our self-love so radical that such “propaganda” must be removed from the internet.

Clearly the prejudice, stereotypes and oppression make self-respect and self-love harder for many of us. Often the love others have for our bodies is what empowers us the most. Focusing on self-respect and self-love is an amazing and necessary revolution within feminism. But in order to free ourselves from the repressive capitalistic version of self-love we need to change the course and put the responsibility elsewhere.

Together we must create a community that respects and celebrates bodies of all kinds. We do that by showing other bodies respect and love. That doesn’t happen until we stop fearing other people’s fat, disabled or trans bodies.

I will leave you with the words of disabled, queer activist Stacey Milbern, who passed away earlier this year at age 33. “I want my legacy to be loving disabled people. By loving each other we start to love ourselves. “

— — —

Embla Guðrúnar Ágústsdóttir is an activist and sociologist. She is a co-founder of Tabú, Tabú is an informal space for self-identified disabled women to participate in activism, share their experience and knowledge with each other and tell their stories, both in saver spaces and publicly available on the web site of Tabú.

No One Would Rape a Fat Woman

My Right to Exist

Líkamsvirðing og fatlaðir líkamar: aðgengisnánd og réttlæti

Rape Culture and The Social Pecking Order

Read more about...