I met with two employees from Bjarkarhlíð, Family Justice Center for survivors of violence

I sat down with both Ragna Björg Guðbrandsdóttir, the project manager at Bjarkarhlíð and Berglind Eyjólfsdóttir, the detective inspector at Bjarkarhlíð. The meeting was covid-style and happened via Zoom. Ragna’s intern got to sit in on the interview as well.

The first thing I asked was regarding the function and goals of Bjarkarhlíð as a resource for survivors of domestic and psychological violence, to find their steps towards healing. We touched on how Bjarkarhlíð mirrors itself with the police force and their methods, the society and other resources in Iceland.

As the theme of this issue of Flóra is mental health, we discussed how violence manifests in the survivors and affects their daily life; the forms of trauma their clients carry with them and what it means to search counselling in Bjarkarhlíð; what the guidance consists of and what happens after.

They addressed the importance of recovery from trauma caused by violence, the importance of the hope we must uphold for survivors of violence and the empowerment towards healing; reaching post-traumatic growth.

Firstly. What can you tell me about Bjarkarhlíð; how it started and how it functions?

Ragna: “The idea for Bjarkarhlíð was brought into the light by a team of strong feminist leaders. The previous Minister of Social Affairs, Eygló Harðardóttir, Sóley Tómasdóttir, then city representative and Sigríður Björk Guðjónsdóttir, former Chief of Police in Reykjavík.”

Both Ragna and Berglind described how the idea was born while participating in a UN Women conference in New York, 2016. As a part of the conference, the Icelandic group was invited to visit the Family Justice Center in Brooklyn, which became the model for the operation that can now be found in Bjarkarhlíð. Eygló, Sóley and Sigríður Björk brought the idea back to Iceland in March 2016 and few months later, more specifically in October/November 2016, a declaration of intent had been signed to open a Family Justice Centre in Iceland. Since 2014, the Police in the capital area, the City of Reykjavík, The Women’s shelter and the Health Care Center of the metropolitan area had collaborated on a project promoting improved procedures within the police force regarding domestic violence cases and raising awareness on the subject. This collaboration, named Saman gegn ofbeldi (e. Combined against violence) originated in the Southern Peninsula Region and was founded by Sigriður Björk before she transferred to Reykjavík. It was an attempt to improve the system for survivors, and it managed to establish itself.

The project’s reception, when starting Bjarkarhlíð, was good and Ragna mentioned how successful these women were, working together — the preparation went fast and smooth, and a year after the birth of the idea, Bjarkarhlíð was opened on the 1st of March 2017.

Ragna: “From the beginning, the ideology was first and foremost to streamline the process for survivors of domestic abuse leaving their perpetrators, and to facilitate access to resources in one place. To lower the barriers most survivors have to climb when searching for help.[…] One place for all survivors of violence — of all genders, not matter how people identify themselves, over 18 years old, for free. […] Another spin-off of the ideology is the collaboration of different institutions and various groups. Interdisciplinary alliance for people in the field, all in one location, joining forces and getting to know each others methods — to develop and customize Bjarkarhlíð to the clients’ needs, with the social aspect, psychological aspect, aspect of law enforcement and legal aspect in mind.”

Berglind pointed out how remarkable the alliance, of different resources, is — all to support survivors on their own terms. Especially from the perspective of the law enforcement — no investigations. The police was solely there to assist survivors and their needs which is something Berglind had never seen before. She believed this to have resulted in better security for survivors as well as boosting the public’s trust towards the police.

Results have shown you being trustworthy and proved to benefit clients. But how do you compare your purpose with the procedures within the police force, especially when viewing your collaboration.

Berglind: “As mentioned earlier, the procedures within the force have changed immensely in regards of domestic abuse cases (and other forms of violence), which aligns with the fact that I am there as a police officer. I report to my station and my department.”

Although. The accessibility and dissemination of information is not the same. Approaching Bjarkarhlíð is much more comfortable and easy, compared to accessing a police station. These types of cases are complicated and domestic violence is miscellaneous. The police rarely receives calls on psychological abuse, the cases expire within the legal system and the police doesn’t always go to the scene of the abuse when it occurs.

Berglind: “You can show up and discuss your situation with a detective […] and the fact that you can come, given an information report on what happened knowing you are not filing a complaint — it is more of an indirect appeal you file against the perpetrator, because the case has expired. What happens is, you report the events that occurred, it is booked into the system and the perpetrator is notified. This alone can have significant meaning to survivors, let alone if the case has expired. You have opened up, told your story, and as often said, delivered the shame to where it belongs.”

Ragna: “Might I add, regarding the association with the force, there is a certain development. With the new procedure in 2014, it changed the whole system regarding domestic abuse cases — the police enters the home and instantly opens up an investigation. […] before Bjarkarhlíð and the new procedure, the police entered the homes repeatedly which fell heavy on the officers’ minds; entering the same places over and over again, nothing happened, nothing changed and there were no resources. As Berglind says, the nature of the violence prevents people from being able to jump out of the relationships with the perpetrators, in spite of the police entering the homes. It takes time for the women [people] to leave the circumstances where the violence occurs, which is in most cases domestic situations. Now, the police has the Social Services along their side and Child Protective Services. As well as Bjarkarhlíð, that became a solid support for people in abusive relationships and the group has the goal to support survivors.”

You can find social workers and detectives in Bjarkarhlíð, and lawyers right?

Ragna: “Today we have three stable employees at Bjarkarhlíð as well as one and a half position from the police. Furthermore, our partners come to Bjarkarhlíð and provide their services from there. Lawyers from The Women’s Counseling and the Icelandic Human Rights Centre, advisors from Stígamót – Education and Counseling Center for Survivors of Sexual Abuse and Violence, counsellors from Drekaslóð, educational and service centre for survivors of violence and their relatives, and from the Women’s Shelter. We also started a pilot project with The Root – Association on Women, Trauma, and Substance Use, this year. Hence, we have a diverse and strong group of people who catch our clients when they go through their story and we help them find a way to work on their trauma within our centre.”

Today we can find various resources in our society — all with the same goals but different approaches. How do you place Bjarkarhlíð within the world of resources? Your focus is on domestic violence and taking the first steps towards seeking help, is that correct?

Ragna: “Surely, many people come to us when they are in the process of realising and admitting their situation as being survivors of violence, which can take long, especially regarding domestic abuse cases. They have been active participants in the relationship for a long time, even years, and have a long history, children even, and they might have circled many rounds in the Circle of Violence. They might have even escaped but returned. […] We emphasize the Trauma-Focused approach, we offer understanding and support to these exact situations; we know how complicated it is to escape violent relationships. Bjarkarhlíð represents this understanding and empathy, as well as our associates.”

Both of them bring up the level of complications with regards to domestic violence, in particular psychological violence. The obstacles, when removing yourself from the violent circumstances, are many. Women, [“One tends to talk about women when talking about survivors of domestic abuse and the majority of our clients are women — although 18% of them are men”] might need more than one attempts to leave but many feel ashamed for entering the Circle of Violence again after exiting before. Matters concerning housing situations, the wait for divorce from the sheriff and custody battles can be weapons in the hands of the perpetrators, trapping survivors and maintaining the violence. This can feel as a cage for the survivors; finding no exits, which is not the case of course. Ragna tells me how survivors need to be in good health, using their full strength to remove themselves from violent relationships — which is rarely the case for survivors after enduring the violence for long period of time.”

What Bjarkahlíð brought when established, was more awareness on the toxicity of psychological violence and its consequences on survivors’ health and daily life. Underlying and escalating violence where the perpetrators systematically humiliate and break down the survivors identity in order to gain power. Having good days and then bad days, later one good day and then many bad days etc. But Berglind emphasises the importance of booking the reports. Survivors find reassurance in having their experiences booked, just in case. The fact that the police now has information on your fear of staying home and information on what you have had to endure; You are in a relationship perfused with psychological violence and you fear your partner or family member. This is often the only action the police can take, without a criminal case there is not much else to do.

Berglind: “In my experience, when working in Bjarkarhlíð, the severity of a long term psychological abuse is one of the most difficult violence to deal with. […] The doubt survivors feel about their situation; ‘is this normal’ or ‘is this an abuse’ — and when reporting to our detectives they had no physical proofs nor any direct threats. […] What was a relief to many is having a place outside their circle, outside their home, to vent. Only mentioning the perpetrators name in the booking was of great importance to them. Being able to tell your story and documenting it in a police report.”

The implementation of the booking is, according to Ragna and Berglind, a critical component of a built-in safety assessment during the first consultation. To revise factors as escalation of violence, in particular when the client is breaking up or leaving the relationship. That moment can be a very dangerous time for the survivors and therefore it is significant to have a police officer present.

Berglind: “I dear to declare that many individuals, visiting Bjarkarhlíð, had no intention of talking to the police. But because the police was there they were ready to talk to our detectives, but would have never contacted the police otherwise. […] There are even cases that went through the whole justice system and were judged in court […] This shows how vital it is to have the police outside the usual frame. Having this cohesive network of assistance in one place. When clients enter Bjarkarhlíð they feel welcomed and embraced.”

80% of Bjarkarhlíð’s clients have a history of trauma, other than current ones, from childhood, other violent relationships and/or sexual abuse. For this reason, many of them didn’t know where to start but what is offered at Bjarkarhlíð is an assessment on each and every individual situation; assisting them to find the most suitable resources, on their terms.

People come for your consultation but what happens after. After Bjarkarhlíð?

Ragna: “The cases are as diverse as the clients. Individuals come for their first consultation which is with the employees of Bjarkarhlíð, and the police if requested. Their case is viewed thoroughly; what kind of service have they had beforehand, where is their mind at and what kind of work are they ready to engage in. And, of course, always on their terms. Therefore the following steps are diverse depending on which associates are best suited to each case.”

Both The Root (Rótin) and The Women’s shelter have the majority of their following consultations in Bjarkarhlíð. That is, clients are offered follow up meetings with applicable consultants as well as lawyers if needed. Stígamót and Drekaslóð offer their first follow up meeting in Bjarkarhlíð but after that, they move it to their own premises. Both The Root and Drekaslóð, throw open houses every week. It is very dependent on the individual what they choose to do after the first consultation but most clients go for a second meeting, with the detectives, the lawyers and/or counsellors.

If individuals are not sure they are entitled to assistance with housing or financial aid from Social Services, a social worker is invited to Bjarkarhlíð to discuss it with the clients — which simplifies the procedure. Having to search for assistance elsewhere can sometimes be too big of a step for the clients.

As it happens, some clients have struggles of such magnitude it exceeds the assistance Bjarkarhlíð has to offer, because Bjarkarhlíð does not offer therapy but support and consultation. Half of the clients have suffered from suicidal thoughts or made an suicide attempt in their life. In these cases they are advised to contact the psychiatric emergency department and/or the Pieta samtökin (organisation who carry out prevention work against suicide and self-harm — and offer support to relatives).

Ragna: “We offer research on other options if needed, in particular the possibilities of financial support regarding treatments for trauma and other therapy options. We direct people to the Social services and the Unions. And not to mention many health care centres offer meetings with psychologists and even connection to the psychiatric teams; Austur (East), Vestur (West) and Suður (South) […] Interdisciplinary teams collaborating with the social services and health care. Very impressive. And we help our clients make connections with these teams if needed, in particular when we can not offer them the service they are in need of. This is part of the evaluation, we as professionals, offer during the first assessments.”

Besides counselling, you do proactive work and create educational material, am I correct?

Ragna: “Yes, but not enough, especially lately. Education on our behalf has dropped completely during these times. We used to throw open houses one Friday per month — inviting various guestlecturers discussing issues concerning violence, bullying and human trafficking etc.”

Both Ragna and Berglind have noticed a huge difference in how many people are involved in the field today, compared to years ago when they were starting. They both find it great to hear so wide range of voices fighting for equality.

During these open houses on Fridays, lecturers such as Þorsteinn and Sólborg (from Karlmennskan and Fávitar) as well as the Slutwalk organisation (Druslugangan) were invited — and many more. By request, employees at Bjarkarhlíð visit high schools, conferences and other events to introduce their concepts and goals. Thus, meet demands rather than using proactive measures, due to lack of time. Bjarkarhlíð is however a member of the European Family Justice Centers Alliance, which uses proactive actions, and has also sent out a campaign on red lights in relationships — and they plan on making more educational videos.

And as a result of good reputation, people, institutions and organisations contact you if they are in need of education or introductions?

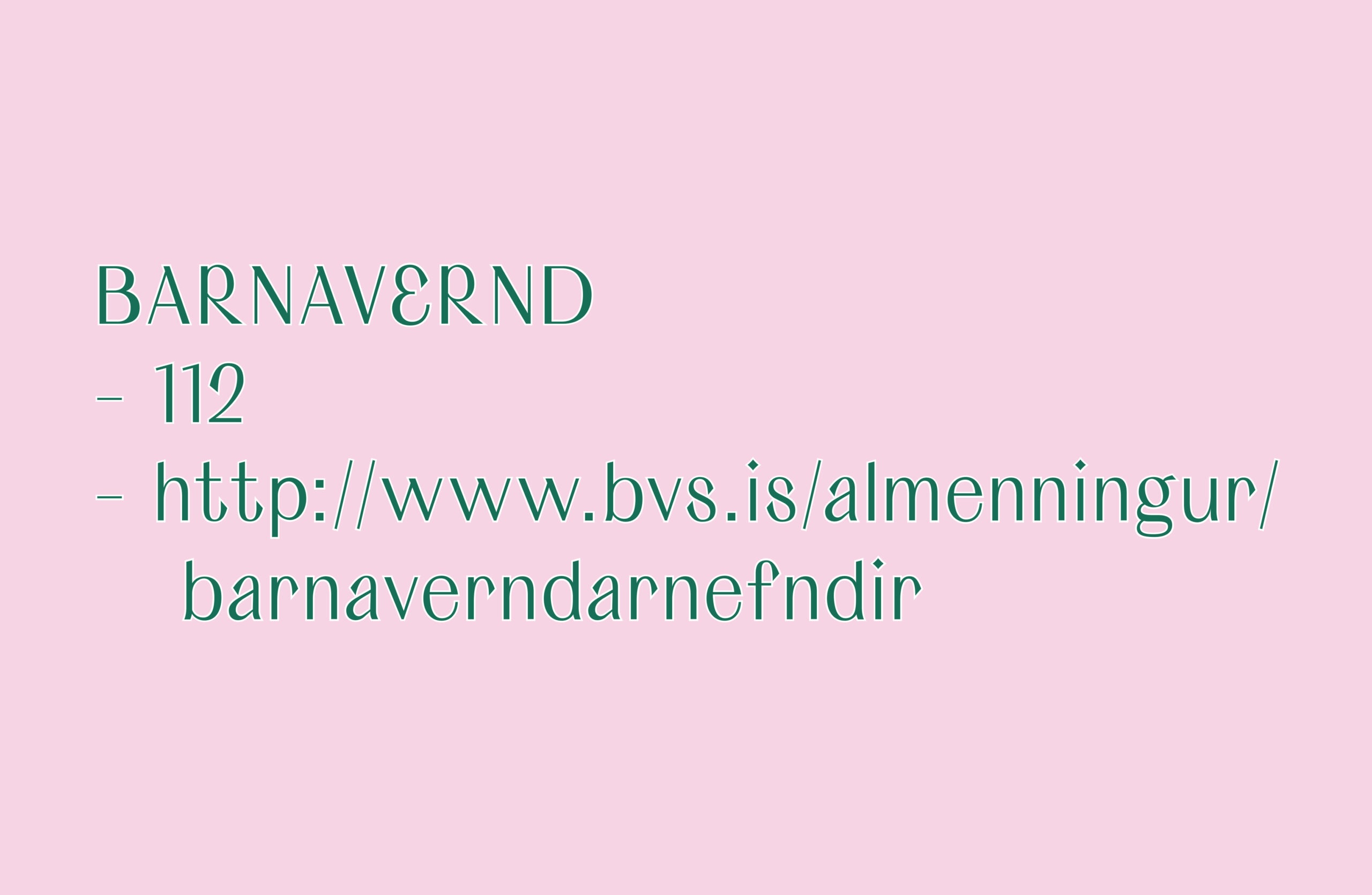

According to Ragna, most people heard about Bjarkarhlíð through friends and family, and unfortunately there is always someone who has never heard Bjarkarhlíð mentioned. But with all the resources offered today, it should be quite straight forward to figure out where to get help. 112 has a new webpage dedicated to information on resources for survivors of violence, as well as 1717, who direct people to Bjarkarhlíð on regular basis.

Ragna: “And we have, as you say, been lucky enough to maintain good credibility, and I hope it stays that way”

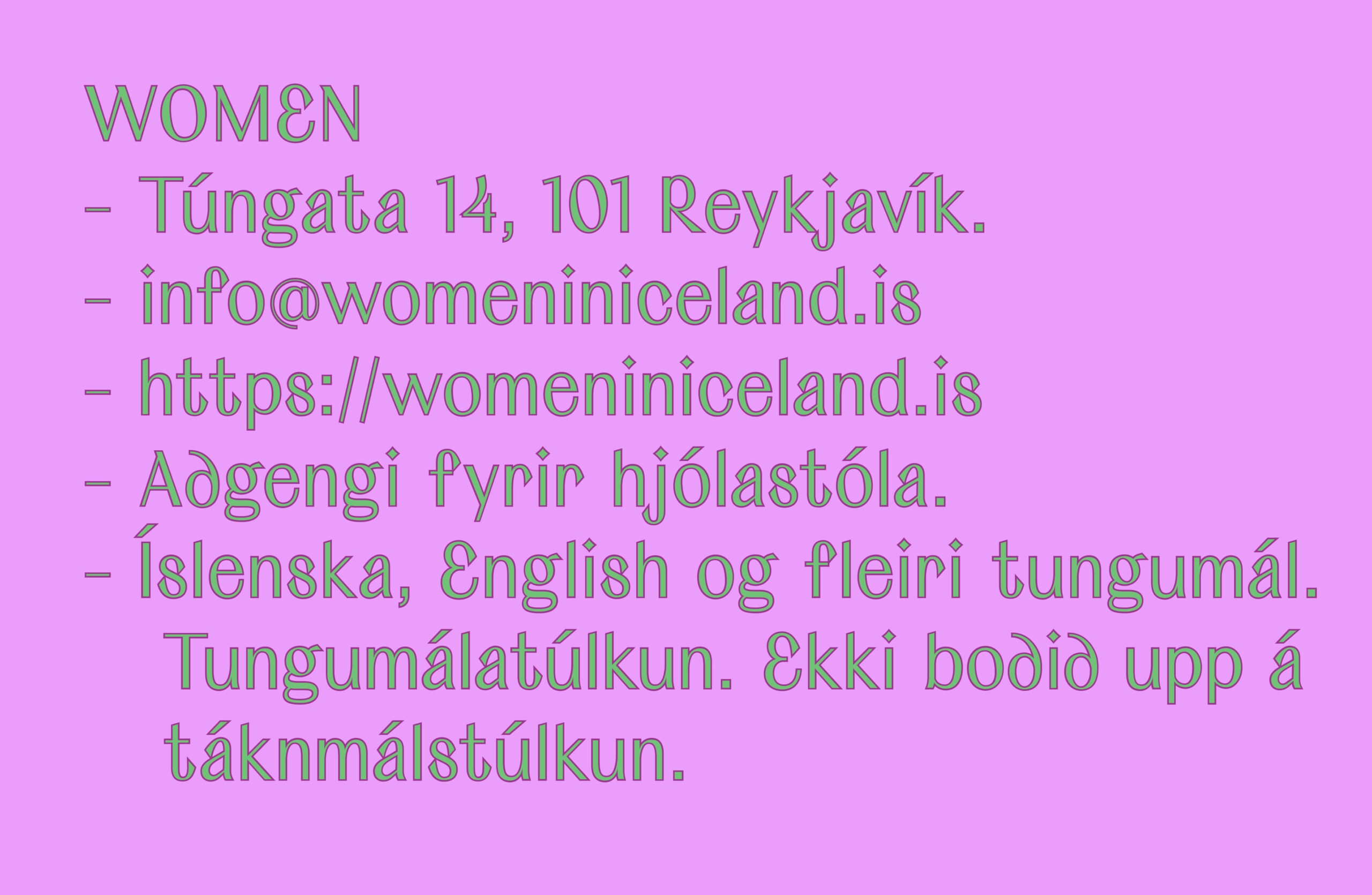

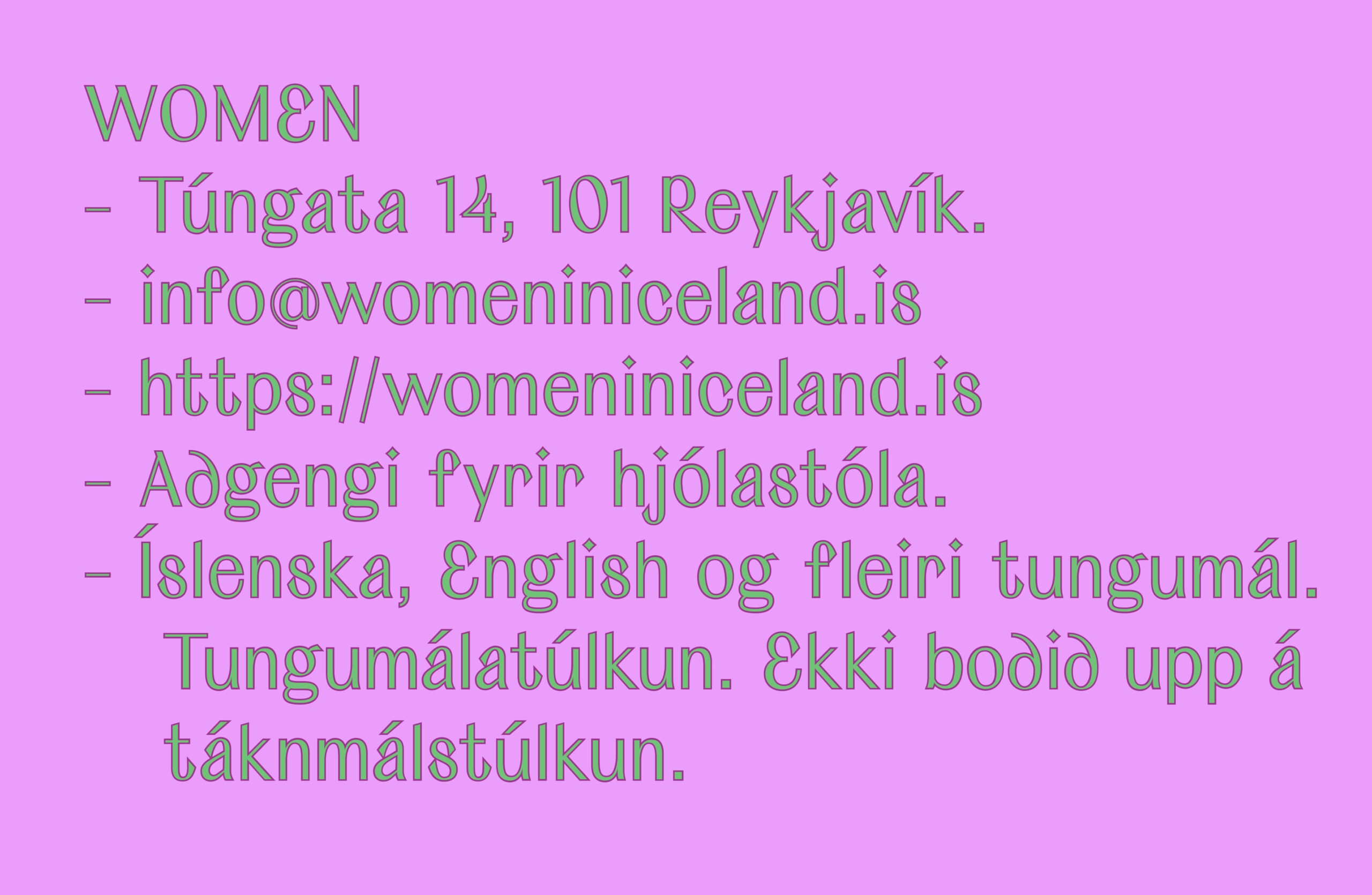

How would you say the accessibility to Bjarkarhlíð is, for disabled people and foreign speaking people for example?

Bjarkarhlíð’s location is ideal due to the fact that is is very hidden within the city, surrounded by trees. And visitors won’t have to worry about being seen by outsiders. The house itself is accessible for wheelchairs, ramp can be found by the building but the parking spot is not paved which could cause problems.

When in need of interpretation or translation, they have contacts with the Language Line Solution. A quick, accessible and good interpretation service. Good first solution. Moreover, when clients bring their own interpreters, Bjarkarhlíð compensates for their service — and they have a partnership with the Association of the Deaf. Recently Bjarkarhlíð received a grant to fund a collaboration with Fatima, interpretation services focusing on the Middle-East and middle eastern cultures. The plan is for the employees at Bjarkarhlíð to receive a course on cultural literacy taught by Fatima.

Ragna: “A group of Polish women gathered on their own terms with the goal to reach out to other Polish women, who might not know the system and might be stuck in violent situation. They got a grant for a collaboration with us in Bjarkarhlíð and throw an open house once a week. Their work is amazing. […] People of multicultural ethnicity count 12-13% of our clients which is at par with the numbers of people of foreign origin living in Iceland.”

What can you tell me about the future of Bjarkarhlíð?

Now when Bjarkarhlíð is no longer a trial project and has been established as a permanent resource, they received a new project. A coordination center concerning human trafficking; the purpose is to map and define the need of service for survivors of human trafficking. And in addition to the continuous development of Bjarkarhlíð’s service, with the demands of clients in mind, the load of Covid-19 keeps rising.

Ragna: “This year we were able to add a new permanent member to our staff. Very necessary. Each year our clientele grows and this year it increased by 30%. These are big numbers of survivors looking for help. And I should add, our biggest concern is if our follow-up is enough.”

It can be ranked as therapy to receive support and trauma-focused counselling — however it is a common misunderstanding to think of Bjarkarhlíð as a therapy center, which it isn’t. Counselling falls under the same category as therapy but there is a difference in degree.

As specified by Berglind and Ragna; similar resources can be found spread around Europe. The one center where the service has been developed what the most, is the Family Justice Center in Antwerpen. There you can find specialists in therapy for people at suicide risk as well as other serious consequences of trauma. As stated before, Bjarkarhlíð doesn’t really offer psychological treatment although Stígamót has psychologists in their ranks. And clients are given instructions on where they can find a place that offers psychotherapy.

Ragna: “But because you wonder how violence manifests in survivors’ mental health, the importance of highlighting this health angle is crucial — understanding just how dangerous psychological violence is to survivors’ health. Understanding the amount of people, who search for help in Bjarkarhlíð, and have already suffered loss of health. They might have made use of resources such as VIRK or other rehabilitation, but people haven’t necessary connected all the dots between their lack of health and the violence they endured. As seen in the ACE study; when being exposed to violence repeatedly or having history of trauma; it makes the survivors more susceptible to further violence as well as future health problems. This comes at a high price for both society and individuals — and affects people in daily life, their dreams and communications. Here we are seeing a gap in resources, information and awareness: the lack of connection, in the public’s mind, between psychological health to manifestations of violence. It obviously entwines and therefore we are very happy to collaborate with The Root, for example. We are seeing a large section of our clients dealing with addiction, alcoholism, eating disorders, self-harming behaviour etc. Other manifestations are PTSD, not being able to concentrate nor being able to sleep or rest, Anxiety, because you are not able to concentrate, sleep nor rest. It is draining to be in distress. It is heavy having to deal with consequences of someone you love, and should love you, being cruel and hurting you. This is all connected”

Berglind: “We have seen in these four years during the operation of Bjarkarhlíð, how important this interdisciplinary resource is to survivors searching for help — knowing you are not alone and having the option to find all help in one place, or so to speak. At least you receive the tools and the guidance towards healing”

Ragna: “One just wants people to understand, to comprehend. And thats what we keep trying in Bjarkarhlíð, treating each trauma and each person on their own terms. We need to be where the people are, plant seeds and to be this message of hope. Even though bad things have happened to you, there is always hope. You have today to rise up, when ready and to get free from the violent situations. To not have the violence and trauma fed for the rest of your life.”

— — —

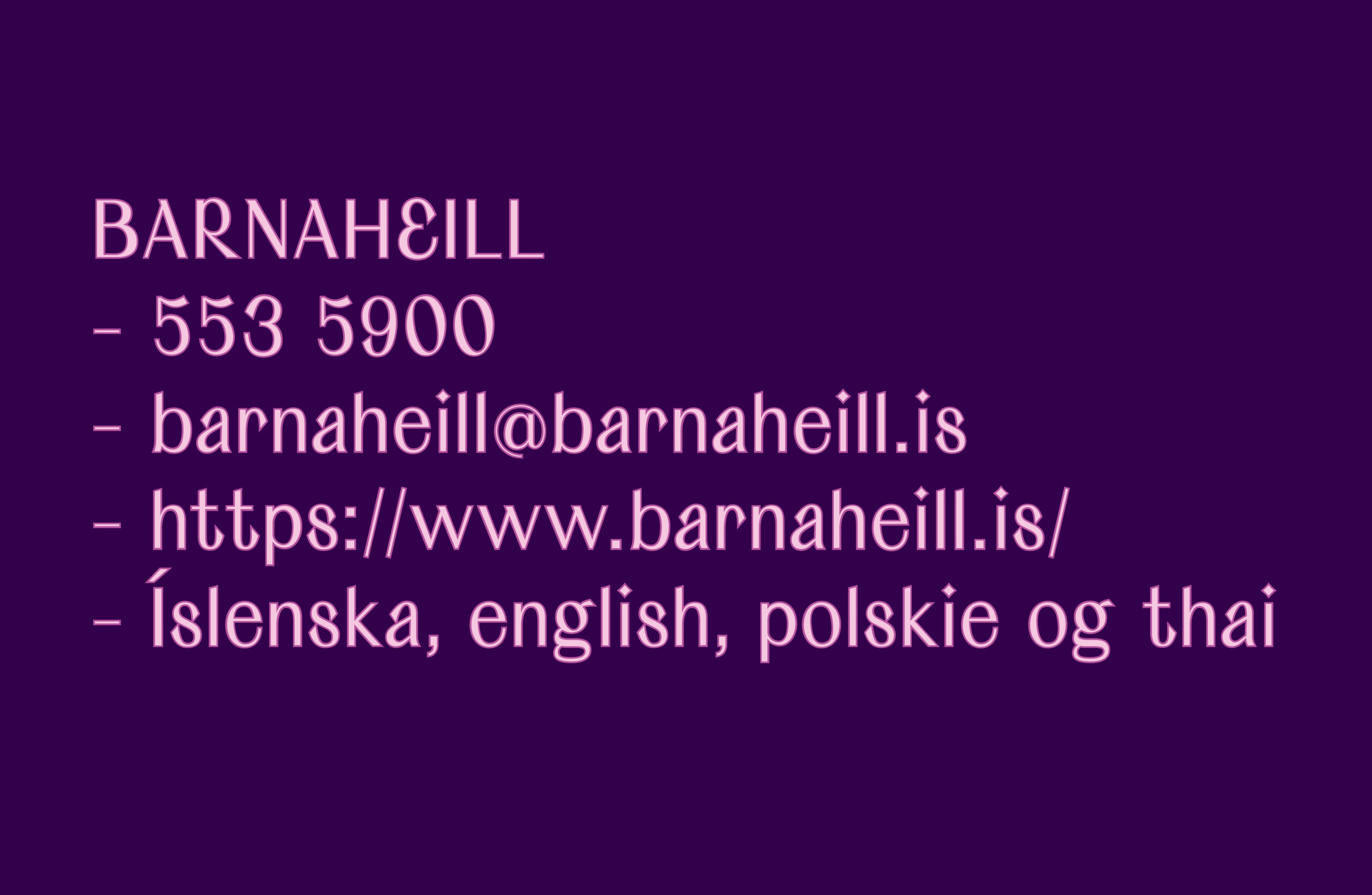

The information on the photos were found on the new 112 webpage: 112.is

Do you support Vía?

Vía counts on your support. By subscribing to Vía you contribute to the future of a medium that specializes in, and puts emphasis on equality and diversity.

Vía, formerly known as Flóra, was founded 4 years ago for critical readers that want to dive underneath the superficial layer of social discussion and see it from an equality, inclusion, and diversity perspective.

From the beginning, Vía has covered urgent societal topics and published issues and articles that have shone a light on inequality, prejudice, and violence that exist in all layers of society.

We emphasize publishing stories from people with lived experiences of marginalization.

Every contribution, big and small, enables us to continually produce content aimed to educate and shine a light on hidden inequalities in society, and is essential for our continuing work.

Support Vía

ADHD: Harmful Stereotypes and Invisible Girls

My Right to Exist

Skilgreiningar: Mér finnst að þér ætti að finnast

The heavy backpack: Being diagnosed with C-PTSD

Read more about...