Elísabet Dröfn Kristjánsdóttir

images:

Stefanía Emils

@stefaniaemils

stemils.cargo.site

translation:

It’s strange how us humans are. Life is like a journey and we walk through it with a large backpack on our back with different experiences either making it lighter or heavier. Sometimes we’ve walked for so long with a heavy load on our back that we’ve stopped noticing and have started working our way around this heaviness. We exert ourselves in a certain way, without even realizing it and one day the backpack has become so heavy; we can barely stand up and we lie or sit and perhaps don’t even understand what is happening — we just feel terrible. That’s how it was for me.

I had realized my load was perhaps a bit heavy, after spending 7 years in a very toxic and violent relationship in my 20’s. I also have a long history of trauma due to being raped and abused as a teenager and a young woman. In this long term relationship, the violence was both mental and physical and it affected my mental health and self-image immensely. It wasn’t until I had my first child that I started feeling how debilitating this weight I carried was, with the added stress and worry of becoming a parent. Like many 2 year olds, my son went through a phase where he hit us, his parents, to see how we reacted to it. During those times I would get these awful flashbacks from violent incidents in my previous relationship.

The flashbacks were so difficult that I would sometimes freeze and then have these crying jags and eventually feel shame over experiencing those feelings when it was my beautiful little child standing in front of me. Something back then told me I could possibly have PTSD but I wasn’t sure. I just knew my reaction was strange. There were other symptoms as well that I hadn’t pinned down to PTSD, such as long term sleep deprivation and nightmares.

I avoid certain music, places and activity and experience disassociation, for example feeling the mind being detached from the body, which results in me neglecting my physical needs and just spending days and months living inside my head.

I can’t bear any sharp noises and being startled can trigger me. There are also other random things that can be triggering for me and cause me pain and sorrow but in some cases I just feel numb. It wasn’t until one and a half years after I had my second child that I was diagnosed with C-PTSD. I had sought counselling at Stígamót because of the violence I had endured and my counsellor pointed out that I had clear symptoms of PTSD and encouraged me to seek further help with a psychologist specialized in trauma. During autumn 2019 I was seeing a psychologist and participating in a very demanding group therapy at Stígamót which caused me to crash because suddenly everything became too heavy.

At the time, I was working as an assistant researcher at the University of Iceland and was extremely interested in my work which demanded my full concentration. I felt very ambitious but suddenly I couldn’t concentrate anymore. It took me a whole day to finish something that usually might have taken me 1-3 hours. It was nerve wrecking and I tried all I could to keep concentrating, but without any luck. I became suicidal, I dreamt of driving alone in my car and crashing into a fence, not necessarily to die but to catch a break from repressive thoughts and emotions.

There is also more understanding of visible illness and injuries in our society than of those that aren’t visible. Fortunately I shared those thoughts during a therapy session at Stígamót, because I felt very ashamed, and they encouraged me again to seek further help. At this point in my life it was necessary to get medication and thinking back, I probably needed even more help and hospitalization — but didn’t realize it at the time.

I was no longer resting or experiencing joy, I would often break down crying during dinner and I would feel ashamed for exposing these feelings to my children, but I couldn’t control myself.

When I finally acknowledged the state of my mental health, I felt a lot of shame.

I remember crying the whole way to the doctor’s office but at the same time I was wiping away the tears and trying to hide them from people I passed on the street. I was prescribed antidepressants and went on a sick leave. I felt like a complete failure and I thought I was ruining my life by telling others about my illness and going on leave, but I would never ever have thought that about another person. The mental collapse was so severe that I had become my worst enemy.

I had these ideas about how people would perceive my illness and the fact that I was staying home all day doing just about nothing. When I turned on the television I imagined the neighbours being shocked and appalled. But of course all this was just in my head, and most likely the neighbours were all busy with their own self doubt. Thankfully I am now in a better state of mind and have adopted the mindset of not caring what other people think. I thought about how difficult it would be to re-enter the job market with a time gap in my CV. Who would ever want to hire a person returning from a long sick leave after suffering from a burnout and PTSD?

Now, I think that I would not like to work for an employer that doesn’t have a basic understanding of mental health conditions.

While I recognize that prejudice against mental illness in our society is abundant, I think my own preconceptions regarding how people would react to my illness was the biggest hurdle. I have found it difficult to explain to people that some things are easy for me while others are close to impossible. There are some things and situations that trigger severe discomfort and numbness, and many of those triggers are related to what I was occupied with before my mental breakdown.

For example I still cannot stay for very long in my home office and I go out of my way to avoid going in there. I find it very hard having to explain to people that my post-traumatic stress disorder is caused by a relationship in my past that ended almost a decade ago. Many of my friends and relatives had no idea of it being an abusive relationship and most people have limited knowledge of trauma and how it affects your body and soul. Traumas are tricky. It’s almost like it curls up in our bodies and then causes all sorts of havoc. It’s like a ticking time bomb or a backpack that is way too heavy, causing a lot of suffering.

Our society is still not ready to openly discuss violence in close relationships and sexual abuse. There is so much shame involved and you feel like you have no one to talk to and no shoulder to lean on. It is immensely difficult to open up and start from the beginning, reliving these experiences and there is also the tendency to be codependent with the perpetrator. You’re never sure if you want to expose the kind of a man he is — so you suffer in silence instead.

Victim blaming is a huge problem in our society — the victim is often blamed for being in an abusive relationship and even considered partly or equally as responsible for the abuse as the offender is, merely by staying. The thing with silence and suppression is that it, slowly but surely, isolates you from other people and you don’t even realise it. Little by little you stop contacting friends and family and then all of the sudden it dawns on you that you haven’t heard from anyone in a while.

When you eventually reach out, people mention how long it has been since you last talked to each other. At that point you feel like you can’t discuss your true feelings because you are so convinced that you are a burden to others. So it’s easier to simply engage in small talk about everyday things, put on the mask that hides your pain and pretend that everything’s fine.

I have been on leave for almost one year and since March I have been in a rehabilitation program at Virk, a vocational rehabilitation fund. The steps towards the rehabilitation program were very difficult but they have helped a lot and are in all honesty the most important steps I have taken regarding my own health. Depression, anxiety and stress are all a part of PTSD and adding to this I got diagnosed with burnout. This is a heavy burden to bear for one person but my task now is to lighten the burden and use positive resources that help me cope with daily life. My psychologist is guiding me through an EMDR treatment which is a powerful way to handle psychological trauma and it has already led to improvements in my mental health.

Slowly but surely the backpack is getting lighter and life is becoming more bearable.

The journey to recovery is not a straight path and with a heavy backpack it is difficult. Tending to your own health can be hard work. At times you feel like for every two steps forward you take one to three backwards, but medication and positive coping mechanisms help with the struggle of everyday life. I feel less ashamed and I try to be vocal about my illness, and the way I feel, with the people around me.

One of the worst things is regretting the time I’ve lost — all that time wasted because of my illness, all that time spent trying to get better, all that time with a person that tried to break me. This feeling of having been robbed of something that I can never get back. I now have a different perspective on life and I can better relate to people that have experienced violence.

This has helped me in human interactions as well as being useful while I was working on my master’s thesis in anthropology. The consequences of violence are terrible and helping others avoid the same fate, and enlightening people about the consequences, is a cause that I now hold near and dear to my heart. The consequences are serious and are possibly one of the biggest health related problems the world is currently facing. We must all become more enlightened.

Do you support Vía?

Vía counts on your support. By subscribing to Vía you contribute to the future of a medium that specializes in, and puts emphasis on equality and diversity.

Vía, formerly known as Flóra, was founded 4 years ago for critical readers that want to dive underneath the superficial layer of social discussion and see it from an equality, inclusion, and diversity perspective.

From the beginning, Vía has covered urgent societal topics and published issues and articles that have shone a light on inequality, prejudice, and violence that exist in all layers of society.

We emphasize publishing stories from people with lived experiences of marginalization.

Every contribution, big and small, enables us to continually produce content aimed to educate and shine a light on hidden inequalities in society, and is essential for our continuing work.

Support Vía

Steps Towards Healing - Interviewing Two Employees at Bjarkarhlíð, Family Justice Center for Survivors of Violence

My Right to Exist

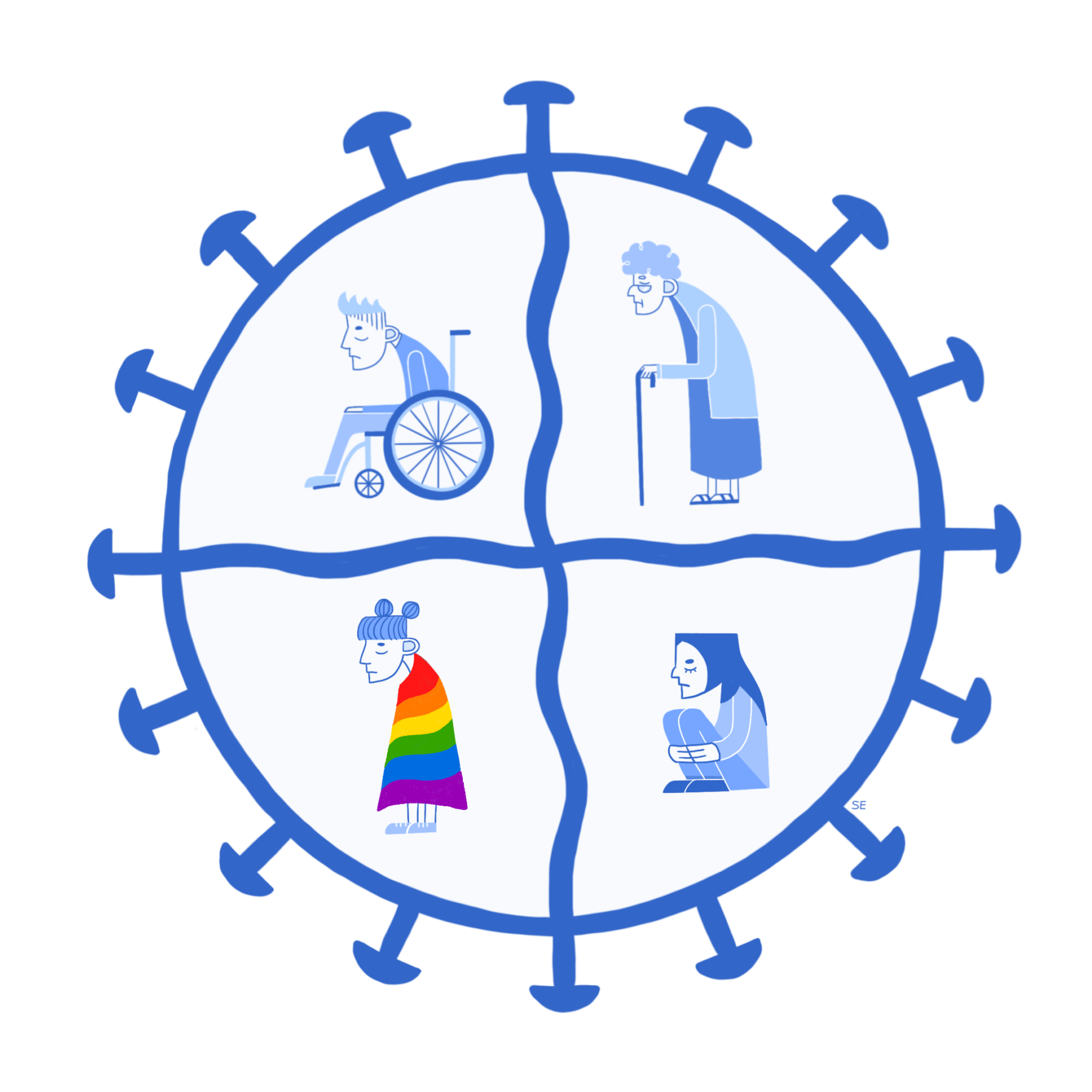

COVID-19: The Virus and Social Status

Bipolar: Three sisters

Read more about...