Table of Contents

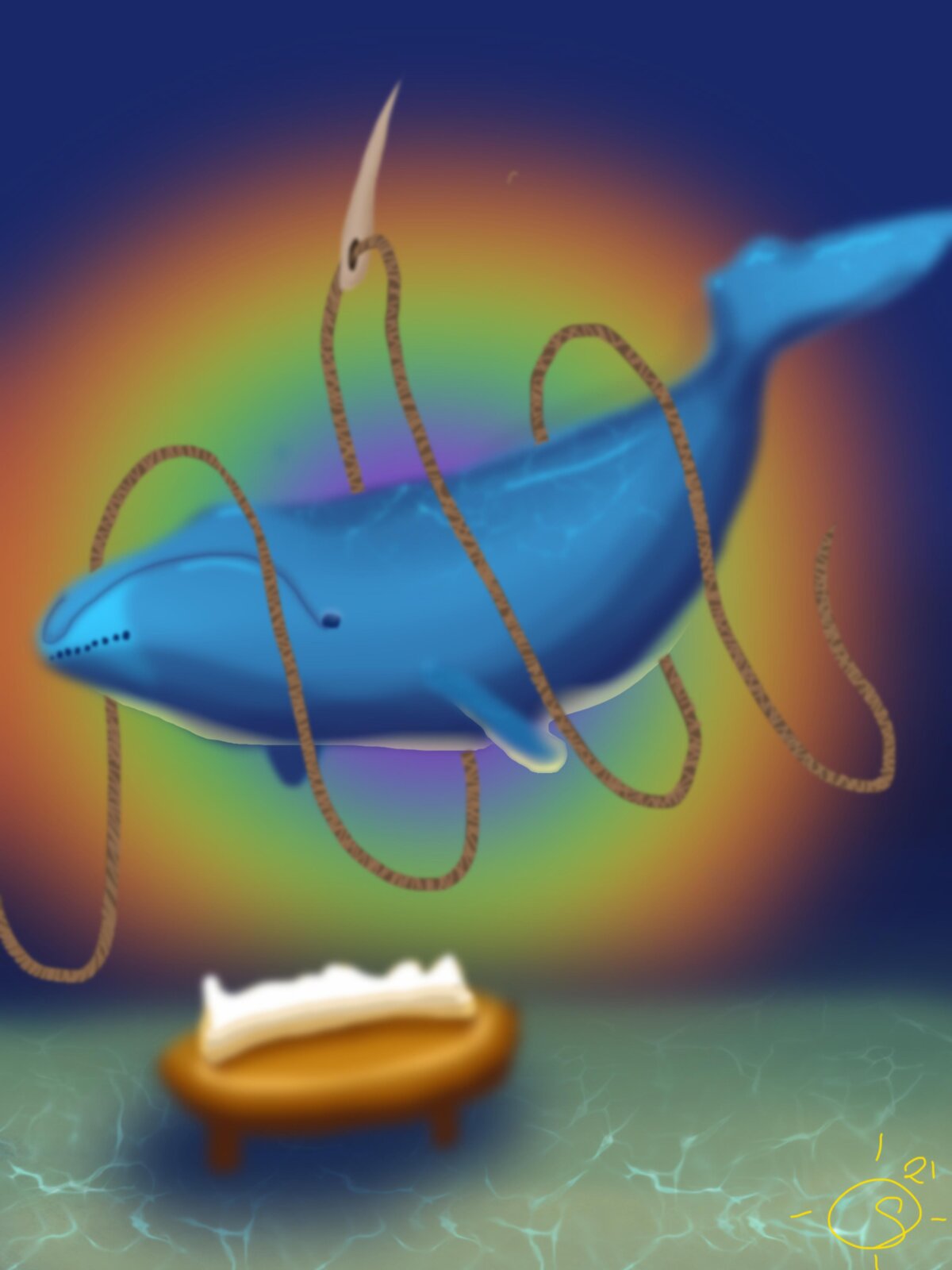

The Inuit women’s personal belongings included the oil lamp and the accompanying lamp chair. This lamp serves to provide lighting: it is oval and not very large. In the past, before the 20th century, the lamp was also used for heating and for cooking. Back then it was usually four times as large, almost round and divided into several rooms. After the introduction of coal-wood fired stoves in the middle of the 19th century, the large lamp slipped out of use. The Disko Bay area was the last place these lamps were still manufactured into the 20th century, while elsewhere, European-made lard lamps made of metal came into use. The lamp continued to serve as a light source in many places in Greenland until the 1950s when electricity was introduced in all towns.

Keepers of the Qulleq – Keepers of light and warmth

My childhood home had electricity. Even Aanaaja’s little home, which had arrived by boat as a prefab build-your-self house had electricity in the kitchen and in the living room. Rooms filled with stories of a life lived in a time of change. Its walls adorned with a combination of the hunter’s display of beautiful pelts and hunting tools and the women’s beaded ornaments placed on every horizontal space next to porcelain swans and plastic flowers shipped in from Denmark. When Aanaaja was young, when she first started having children, she still had to carry out all her chores in the light of the Qulleq, the soapstone oil lamp.

She was the keeper of the light and the warmth of the house. A woman’s task. An important task filled with spirit that went back to the beginning of times.

A woman’s personal belongings included the soapstone lamp and the lamp chair. As a light source, the oil lamp was used in many parts of Greenland until the 1950s, including in Aanaaja’s house, until electricity became available. The use of the lamp had already been reduced to a light source when the coal-wood fired stove was introduced and the lamp no longer was used for cooking.

Despite these changes, many of the chores remained, same as ever. When I was 8 years old I would sit on the coal box in the kitchen and watch Aanaaja butcher seals. Her experienced hands would cut open the underside of the seal in a straight line from tail to chin before moving to loosen the skin on both sides. The thick delicious layer of pink blubber shined bright underneath the silvery coat and made my mouth water. Such an important resource. Precious and valuable fat that fed people and kept the Qulleq fuelled through all times.

Along with whale blubber and baleen, seal fat was the most important commodity to the Danish colony.

Who knew that back in the days, the Europeans were lighting up their big cities with the same fuel that we used in our humble little lamp, the fat from our precious sea mammals. I certainly didn’t know any of this as I sat there on the coal box in Aanaaja’s kitchen, learning to butcher seals by watching her doing it repeatedly. Just like little Inuit girls have learned by watching women do for thousands of years.

Coming of age in the time of the Qulleq

The difference between me and those little girls from the time before the colony is that I had a danish father and I was not about to get tattooed by Aanaaja. Aanaaja was Christian like everybody else in 1970s Greenland. Our ancestors had long ago abandoned the practice of body marking which was a significant part of Inuit spiritism. Aanaaja did, however, teach us bits of the spiritism and to my father’s great annoyance she would feed me raw seal liver for strength and the seal’s eyeballs for good eyesight, right before dinner. My father would scold me as I returned home at the ordered time, with fresh seal blood on my face.

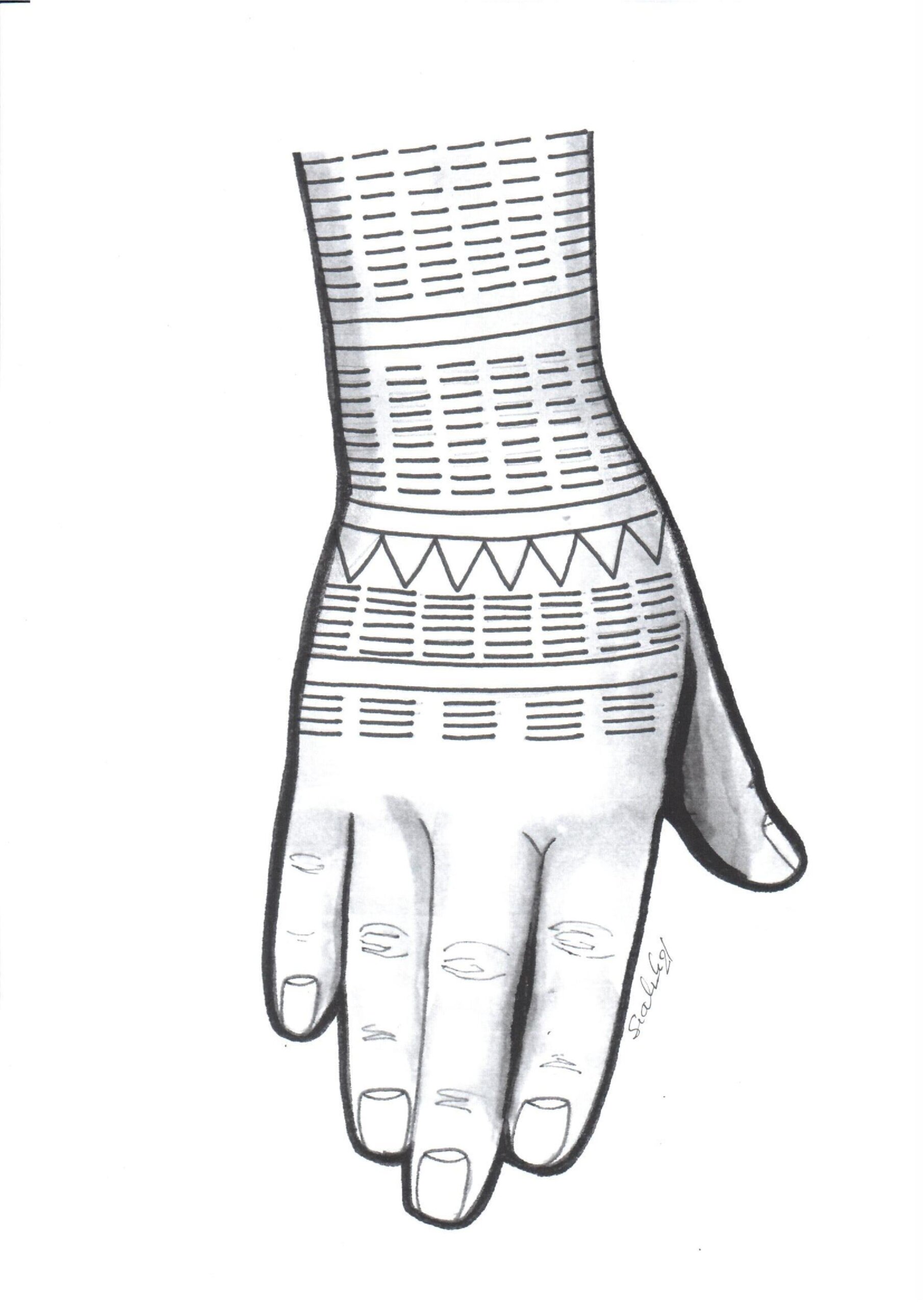

Had I been an 8 year old girl before the colony, I would most likely soon have received my first chin lines to show that it had been decided that I no longer was a child. The rest of the tattoos covering the front of my body would follow shortly. Amongst them would be the amulets of the Qulleq on my arms and thighs.

As my elder, Aanaaja would have started applying the markings on my face and body with bone needles and sinew thread dipped in a rich pigment made with soot from the burning fat from the Qulleq mixed with the urine of my elder woman. These were patterns as old as our perception of the sky and the ocean and they granted balance between the worlds of the humans and the spirits. More women would follow, my mother and aunts perhaps, also I would complete some myself.

The important part was to complete all of the tattoos before joining the ancestors in The Land Of The Happy. Women with no markings or poorly made markings, along with lazy hunters, would end up in The Land Of The Hanging Heads. A terrifying threat.

Myths, legends and the creation of worlds

The Qulleq is mentioned again and again in the thousands of myths and legends of the Inuit lands. It plays key roles in the creation of the sun and the moon as the place from where the young woman Maliina grabs the burning moss before she takes flight into the sky and becomes the sun after her brother Aningaaq is revealed as her rapist. He, in a similar way, holds burning moss from the Qulleq as he runs after his sister into the sky and becomes the moon. The burning moss in his hand was blown out, but its glow remains in the sky as the shifting shape from crescent to full and back, dictating the reproductive cycle of women.

Evangelization and colonization of Greenland

The stone lamp was used all the way into the 1950s in the Disko bay area where my childhood took place. The tending of the flame and the economics of fuel spending were taught from woman to woman-child for thousands of years. It was quickly forgotten when the petroleum light came and it slipped further into the realm of history when electricity was installed in our homes.

Today it holds an almost ceremonial status. An icon of our culture that has lost its importance in daily life. This year marks the 300th year since the evangelization and colonization of Greenland began. Acculturation is still in effect and it is hard to distinguish between what is new and what is old knowledge and truth. We live with a collective sense of loss without remembering what exactly it is that we have lost.

Our material culture, the tools, the kayak, the dogsledding, the clothing, the carvings, the embroideries, has been abundantly described.

Meanwhile, the intangible parts of our culture were discarded and abandoned as primitive and without value. Therein lives the sense of loss.

How did our ancestors think and experience? What was their worldview?

What parts of my worldview have roots in the continuity of our relationship with land and ocean? We struggle to discern contemporary values from ancestral values. Today Inuit are asking each other questions in online forums “why are Inuit not allowed to sew on Sundays?” “Did your grandparents say prayers while hunting?” The replies often only serve to amplify the confusion.

The Qulleq

On the side of the benches in front of the bed is the fireplace, which consist of a stone lamp and a framework from which the pots are suspended. The lamp (Qulleq) which is made of soapstone, is a shallow vessel in the shape of a small segment of a circle. Sometimes a small space is divided off at the back for gathering in the scraps of blubber.

Franz Boas. The Central Eskimo (1888)

The Qulleq – as described in its material form. Carved out of the precious soft soapstone often gathered far from the settlements or bartered for at the summer gatherings of many clans. A spirited stone that holds on to the warmth of the flames and contributes to a comfortable temperature in the tent, the sod house or the igloo. The wick is material gathered during summer. Mostly dried moss and tundra plants but hair or dried excrement of the arctic hare also worked quite well.

Boas continues his descriptions and can’t help but to express some personal opinions on the use of the blubber; In winter the blubber is frozen before being used, after which it is thoroughly beaten. This bursts the vesicles of fat and the oil comes out as soon as it is melted. The pieces of blubber are either put into the lamp or placed over a piece of bone or wood, which hangs from the framework a little behind the wick. In summer the oil must be chewed out. It is a disgusting sight to see the women and the children sitting around a large vessel all chewing blubber and spitting the oil into it – Franz Boas. The Central Eskimo (1888)

The Europeans have always regarded Inuit as crude and primitive and once stuck in that mindset it is hard to see what an ingenious invention the stone lamp actually is.

In the treeless Arctic tundra, covered in snow and ice most of the year, the Inuit devised a source of heat and light. A fire made without firewood. Inuit are a people who have specialized in living in the Arctic and have over thousands of years perfected technology and hunting skills in an environment where the game is low in variety but big in numbers and under the control of the seasons.

Only very few of the arctic animals stay in the Arctic all year round while the big herds of caribou, just like the sea birds and the great whales, migrate south during the long winter period. During this long wintertime, Inuit are left to depend on seals that are hunted through their breathing holes on the frozen ocean and the few land animals that stubbornly remain on the tundra all year round.

The summer hunting serves to build winter reserves of food and materials to make clothing and tools from, but often it wasn’t sufficient and the very real threat of famine loomed large in Inuit life.

As the lamp and humans share the same source of fuel, famine also brought on darkness and cold. The kaperlak is relentless, it is a time when the sun does not rise above the horizon for weeks and weeks. The landscapes are bathed in shadow and crushing cold. The humans in their sod houses or igloos huddle in similar darkness. Hungry and laying close to keep each other alive with body warmth under the bed skins.

Survival in the arctic is part technology and part spirituality. The amulet is just as powerful and necessary as the harpoon and the sewing needle.

The man wears his amulets in his clothing and attached to his tools. The woman’s amulets are tattooed into her skin, in rows of horizontally placed patterns from fingers to shoulders. From ankles to upper thighs. Never touching the joints, placed precisely and according to rules dictated by the ways of the ancestors.

These tattooed amuletic patterns representing sinew thread, hunting tools and the Qulleq ensured good hunting by keeping the spirits in a mild and generous mood and thus shortening the periods of famine when the stone lamps also sat idle, unlit by the beautiful row of flames which resemble a mountain range.

Tattooing and the long-forgotten and then remembered culture

Aanaaja did not tattoo my skin when I was 8 years old. She didn’t tell me about the tattoos of our ancestors because she didn’t know. It was long forgotten in the Disko Bay area in the 1970s. She taught me all the things that weren’t forgotten and the many things that Inuit always did although in her time we no longer remembered why.

I learned to wake up the spirits in my fingertips by sewing tiny replicas of traditional hunting clothing and I learned beading and cooking traditional food. I learned to enjoy eating outside on summer nights under the midnight sun while taking in the sight of the generous ocean and feeling gratitude. All those cultural aspects I took with me into my adult life and one day against all odds a white, tattooed person, far away from my homelands, offered to teach me tattooing.

After a lengthy formal apprenticeship and many years of western commercial tattooing, I started researching the tattoo practice of my people. It has been quite the overwhelming experience and it has led to my complete abandonment of western tattooing. I left the tattoo machines and the tattoo scene behind and learned to study, disseminate and practice the old form of tattooing from the Inuit lands.

Shared, neglected and stolen Inuit cultures

Over the last 11 years, I have tattooed countless numbers of Inuit women from many of the Inuit territories.

We all have things in common despite being from different tribes across different territories. We share mythology, drum dance, storytelling and tattooing. Immaterial cultural aspects that run through the Arctic like a common language with many dialects.

We also share the Qulleq and we all understand its importance and significance. We still know as women that we were supposed to know how to tend the flame and how to be economical with the precious blubber fuel. We understand the ancientness and the spiritual power of the Qulleq as it is represented in the myths that describe how our world began. But we haven’t learned to tend to the flame. We don’t all hold a stone lamp amongst our personal possessions and we never cook over the flame or have the lamp as our only light and heat source.

The Qulleq has faded from the daily life of an Inuk woman and is now regarded as ceremonial and only used on special occasions.

An elder woman will light the Qulleq at openings of parliaments, exhibitions or at talk circles where Inuit meet to address culture and politics. Sometimes the lighting of the sacred lamp is accompanied by a prayer to the Christian god and is thus stripped from the last bit of its old spiritual significance.

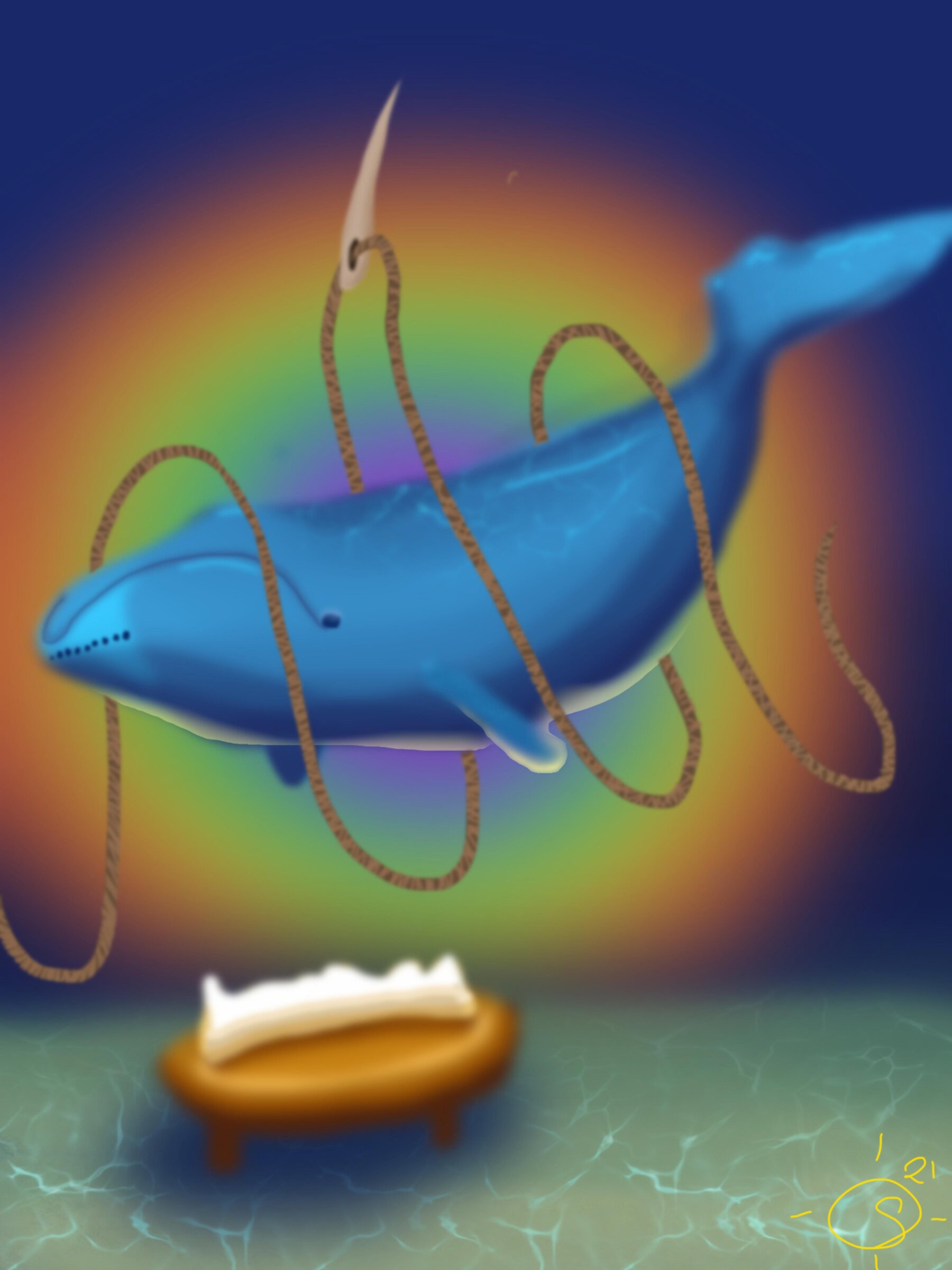

This led me to create the artwork Qulleq. An Inuit oil lamp crafgted out of metal rather than soapstone and left to rust and deteriorate. We will never lose the lamps made of Soapstone, they decorate homes and public buildings. They are exhibited in ethnographic collections in museums.

The rusty lamp represents the neglected spirituality of the Qulleq rather than the physical lamp itself. It evokes the dilution of the religion surrounding the women’s daily chores. It speaks of the loss of the women’s spiritual power and social importance as the Christian patriarchal mindset displaces the Inuit worldview and matriarchal construct. It represents all my mothers back to the time when the first humans fell down on the tundra from the sky and started creating babies with Nuna, the land.

Fagurferði hversdagsins

My Right to Exist

Decolonizing gender – Myths, beliefs, and acceptance of fluidity among Inuits

Tannár - Buffalo skógvar, sjeikar og spik í '90inum

Read more about...