Erling Kjærbo

@cyber_librarian

images:

Theresa K. Jakobsen

@pinkudreyma.welt

pinkudreymawelt.com

I look into your eyes; I know what is about to happen. I am ok with it. I am a big boy, and this is what we do. This is what we have always done. My grandfather pulls the trigger, then grabs the knife, opens your throat, and your fresh blood gushes into the bucket.

“Don’t cry child, it’s ok. You must stir faster! No, not like that… do it like this…”

My grandmother will make pudding with your blood. It is slaughter season for Faroese sheep farmers, this is the reason for your existence. You are the first of many. Behind me, other male members of my family are ready to skin you, and your kin.

We will use every fiber of your being purposefully. Your brain will be mashed with potatoes, your eyes suckled, your tongue cooked, your face cut in half, then charred and later boiled. Everything from your head to tail will be used. My sister and I are going to play with your hooves, and your bones will be used as toys by my cousins. As empathy overwhelmed me, I ran out, and since then, I never willingly took part in the killing again, of anything.

I never forgot that feeling. I was overwhelmed by emotions, I was frightened, confused, filled with sorrow and adrenaline. My body was shivering, nausea kicked in, everything around me went white.

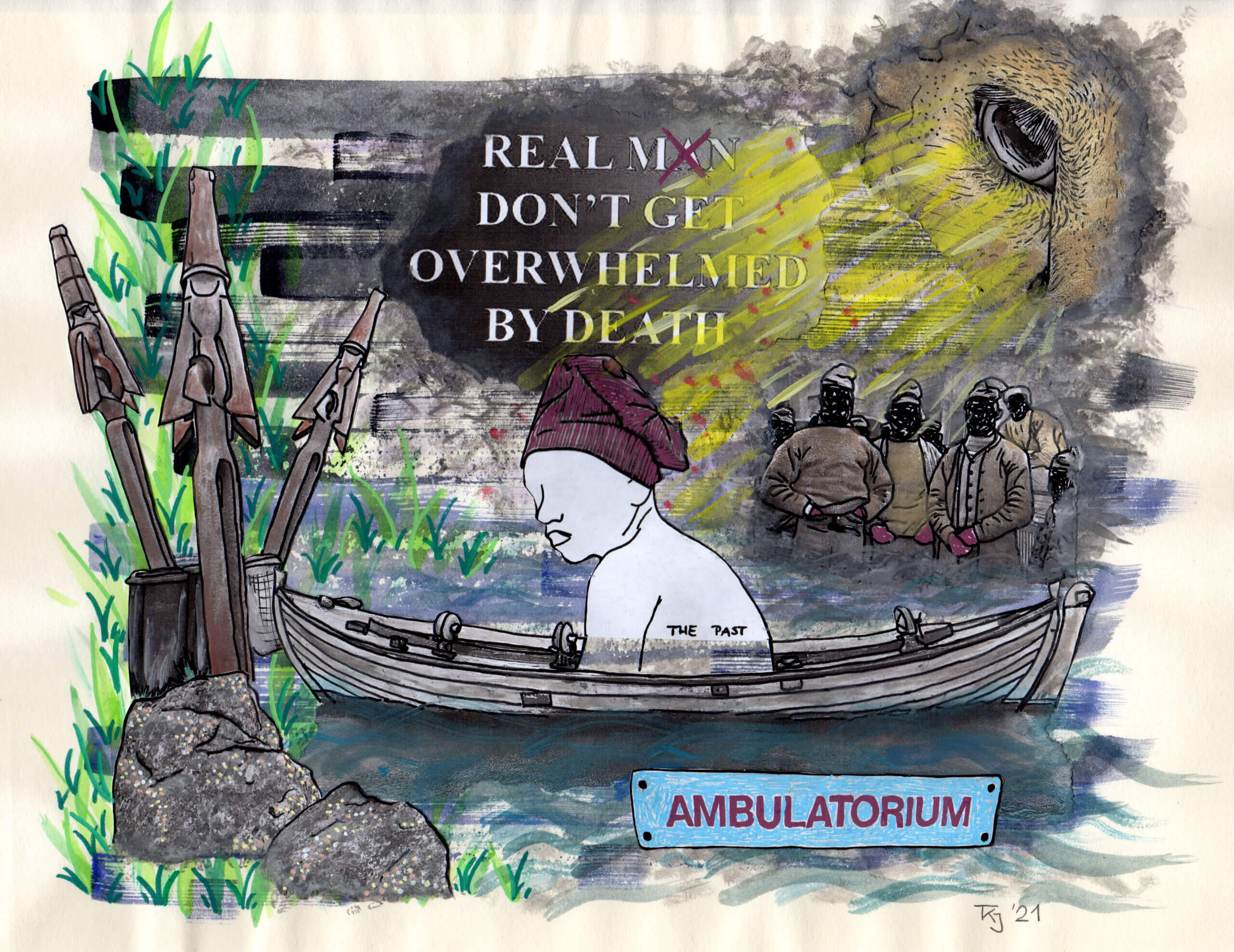

“It’s okay child, don’t cry”. Real men do not get overwhelmed by the death of an animal.

I have always been very in touch with nature. My family used to mostly live off the land. Meaning everything on our table was from our lands, the sea, or the skies. In a way, I have always been seen as the black sheep of our family. Because I largely have not conformed to the family’s traditions. I had no interest in hunting, fishing, or raising sheep.

I spent a period of my life, from when I was 5 until I became a teenager, living in Denmark, mainly in what was then a ghetto. My father died when I was three, and I grew up with my mother, sister, and a few stepdads. I would go back to the Faroe Islands in the summers and eventually ended up moving to my grandparents at 14. Mainly since I had always had a deep longing for “home”. But maybe living in the “concrete jungle” somehow corrupted me?

“Hold the bag, open it wide” I struggle with the zipper, feathers are flying everywhere, and the basement is filled with the continuous chorus of shrill cries, hoarse honks, and high-pitched quacks, as Olgar the Goose is about to meet his executioner. I was not a big fan of Olgar, he had been driving me crazy from outside my bedroom window for many months, but I still cared for him. I had seen him and his partner Olga, raise their goslings each summer for the past many years.

I wondered if he knew what was going to happen in a few seconds. Olgar was in the bag, I closed the zipper, so only his neck and head came out. My grandpa killed him. Olgar kept flapping his wings, although severely restricted within my old gym bag, for a few seconds. I turned away, and a tear made its way down my chin, he was gone. “Don’t cry, you’re too soft, come… we’re getting the other one, bring the bag”.

I have never really considered what masculinity was to me, and what it meant to me, until recent years. Manliness to me, was always about strength, bravery, power, providing for the family, leadership, and being head of the household. And most importantly, hiding your emotions in a stoic medieval way. At least that is the view I used to have. I always strove to be a “real man”, hiding my insecurities and being paralyzed by fear because of what I assumed my family and friends would think of me if I let myself be vulnerable.

Then I just stopped trying, and for many years, I felt like I was not a real man.

It is 07:20, my alarm goes off. I get up and sit next to my grandfather, while my grandma makes us breakfast, she pours coffee into our cups, and we all light our cigarettes in what has become a family morning ritual – nothing beats a Marlboro light, with a cup of coffee and a cheese sandwich. The kitchen gets filled with the smell of cigarette smoke, coffee, and fresh bread.

My grandpa starts talking to me about our sheep, and I zone out, now and then I face him, nod, and smile, when he asks me what I think, I just shrug and say, “I don’t know”. My grandma served us food and took our plates when we were done. “Did you clean my brown boots?” He asks her, she nods. We grab our gear, which had been neatly prepared and cleaned by my grandma last night, head out to our blue Daewoo and drive down to the fish factory.

I work there during the summers, and yeah, so do my grandma and grandpa. One last cigarette before we head in. Most of my friends work there as well, and so do their parents. I cannot stand the smell of fish; I hate everything about it. But I feel like everyone in my family will look to me as being diligent if I pretend like it does not bother me. Next week I am going out to sea for two weeks as a greenhorn, on a fishing trawler that a family member is captaining. This is what the men in my family have done for generations.

I remember when I was younger, I would hear of women joining the fishing boat crews, and how negative the reactions often were to that. That is not a job for a woman, right?

I have worked in libraries for most of my career. A field historically entirely dominated by men, but now most students accepted to the Library and Information Studies are women. And the stereotypical librarian is now portrayed as a woman, wearing her hair in a bundle, with glasses, a shirt, and a sweater-vest, pushing a book cart, shhh’ing patrons. Whereas the opposite a few generations ago was the all-knowing middle-aged male information gatekeeper, akin to the librarians in Umberto Eco’s literary masterpiece “The Name of the Rose”.

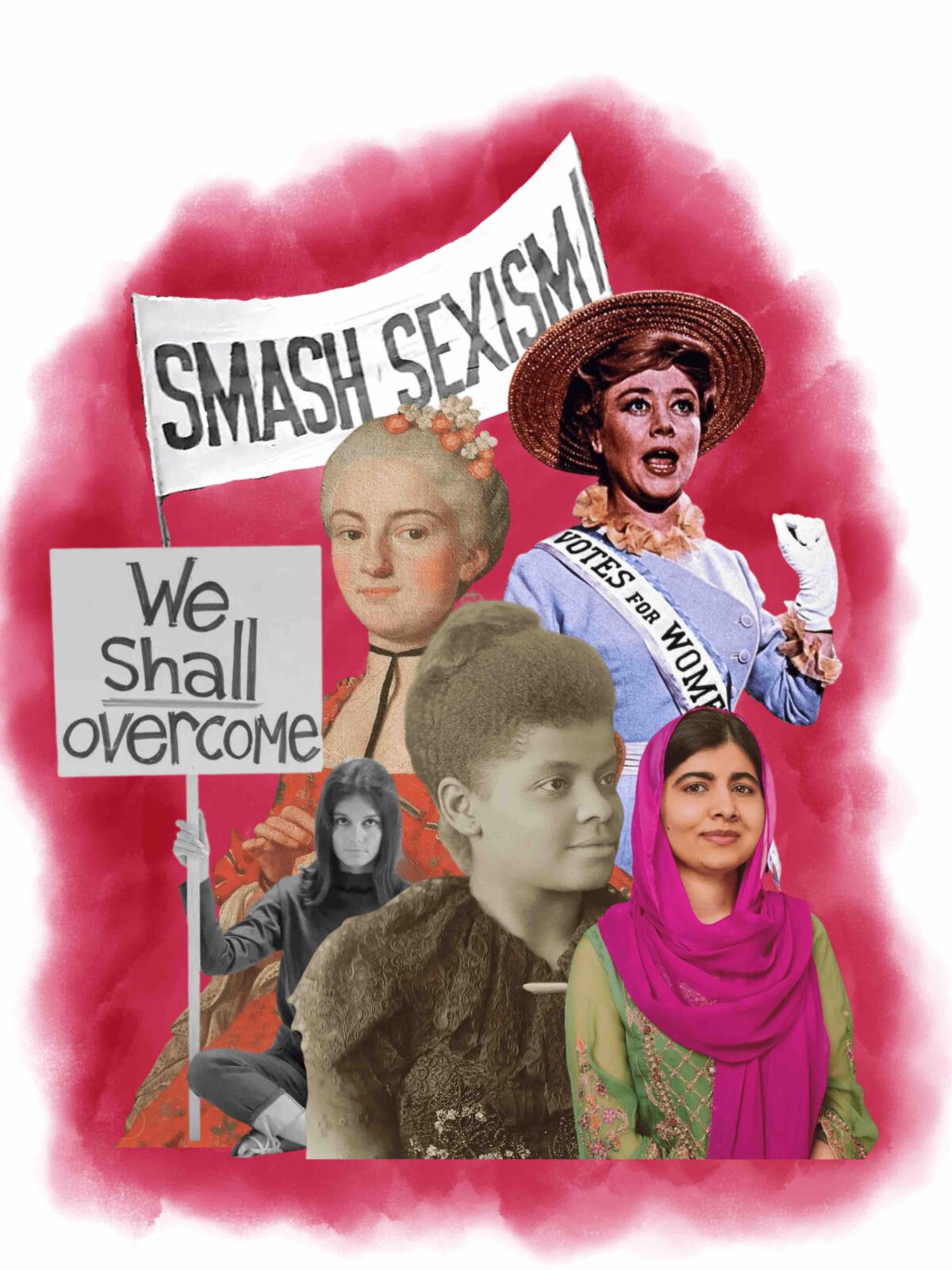

The same is happening in many other professions, as careers that before were stereotypically male or female are now blending, or completely overtaking the other. A view of librarianship as being something masculine has washed away, because of changes in our society and because of our fight for gender equality.

Globalization and the emergence of the information society, where we share, use, and create information has changed the world in such a short time. The leaps we are taking in science are shaping our governments and making us rethink the structures of society. It’s such a short time since social media first made an appearance, and now we connect thoughts and opinions at lightspeed.

I feel sick. I was out drinking with my friends last night. I do not even remember how or when I got home. I crawl out of bed, and make my way into the hallway, trying not to wake up everyone else. It is pitch-black, I have no idea what time it is, but if I turn on the lights, everyone will wake up, as the doors do not keep the light from shining brightly through the openings in the door frames. There are 6 bedrooms on the top floor, and from most of them, you hear heavy breathing, snoring, and now and then the sound of people moving in their beds, or sleep-talking.

It is an old house, going back three generations. It cracks, aches, and yawns in the wind, but it is sturdy, and weather tested. There are about a hundred houses in my village, all built to withstand the Faroese forces of nature. The village has stood for a thousand years. I know exactly where to place my feet on the floor, so the wood does not squeak. I know which steps to skip on the stairs, I know exactly where to put my weight, and where to tread lightly, going up and down. I have it all in a song in my head, to the tune of the Navy song “I-don’t-know-but-I’ve-been-told”.

I reach the bathroom door downstairs, this door will make a sound, no matter what I do. I hear something stirring upstairs after I open and close the bathroom door. It must have awoken my grandfather. I barely keep my balance in the bathroom as I relieve my bladder. I gracefully make my wood-squeak-free dance into the kitchen and drink a big glass of milk that we get delivered in a bucket, every morning, straight from the udder of the neighbor’s cow. And I then proceed with my intricate and ceremonial dance, back up the stairs, into my bedroom.

I open the window, light up a Marlboro, and sit here, in my safe space, looking into the ocean surrounded by cliffs and mountains. In a few hours, everyone will get out of bed, we are going to the mountains, to herd the sheep flock down into the valley, so we can shear their woolen fleece, and give them medicine. As I flick the cigarette down into our neighbor’s yard, it starts to rain, I love the rain. My room is located under a half-roof, and when the rain gently patters on the window and roof tiles, it creates an ambient blanket of comfort. Rain means fog, and you cannot herd sheep in fog. I smile as the rain lulls me to sleep, and I drift off.

In my optic, life at home was always about sheep. I remember countless family birthdays and similar gatherings, where we would have many guests, and all the men would gather in the living room and talk about all things sheep, “what ram weighed the most during this slaughter season, which ram should be the breeder this season, who owned the three ewe’s that always ran close to the road on the way to the lighthouse? Have you tried importing hay from Iceland? Was the old, red-horned ewe still alive? Which ewe had given birth, and what color and gender the lamb was? They would take turns asking these questions. So nearly all the male role models in my life growing up were very passionate about sheep. Something I could not relate to, or conform to, at all.

For these occasions the women of the house would have baked, cooked, made coffee and tea, always making sure there were clean plates, and that the table gets emptied, so a new round of guests can take the table. They would be helped by the other women, and they would all hang out in the kitchen, talking about womanly things, whatever that is. I always ended up in the kitchen, partaking in the conversations there, and also getting the attention of aunts and cousins, asking me about what I had been up to, and how school was going.

A big part of me never liked these gatherings, I always felt so out of place.

Most of my friends would go traveling for the summer. I would work the first part of summer, often at the fish factories, and then the latter half of summer, my cousins and I would spend helping our grandfather with the haymaking. From mid-July till mid-August, was haymaking season. I have a very ambivalent relationship with it, as a kid I loved it! As a teenager I despised it, and as a grown man I romantically reminisce about it, reliving fond memories of the whole family being together, with a lot of them passed away now.

All of us raked grass into piles, letting it dry to turn it into hay, make hay piles, then spread it out again to dry it some more. The memory of my grandmother bringing us all pancakes, waffles, and warm lunch. Dragging plastic sheets of hay down the hill, to the lorry on the side of the road, fill it up, and ride the lorry down to our barn, where we would put all the hay into the hay well. Rinse and repeat.

We would spend morning to afternoon on the mountainside, for a month, every day, every weekend, apart from Sundays. God did not allow my family to do physical labor on Sundays. Now and then, I would be told that I was doing a good job by my grandfather, which in return filled me with pride and a sense of manliness. I helped every summer until I went to study abroad. I hated haymaking, but I would get so much praise. What a man!

I am watching Hornblower on the television with my grandparents. Grandpa is sitting in his chair, and I am laying down on my favorite sofa. The phone rings, I answer, some relative is frantically screaming “Grindaboð!!” at the other end. I get equally excited and jump up and down repeating the same word, my grandma is ecstatic, and can barely contain her excitement as she rushes to find our clothes.

In one swift movement, my grandpa jumps up from his chair and nearly pushes my grandmother over, as he takes big steps, rushing towards the spiral staircase to get into the basement, all while the three of us are screaming the same word “Grindaboð”. The basement is where we keep the gear, the knives, oilskins, the big bowls, and buckets. 5 minutes later, we are down at the harbor, with hundreds of other people from the island, waiting for the boats to come as they herd the whale pod into the bay. We do not partake in the actual killing. My grandparents are too old, and well, I have never wanted to kill anything! But I see my cousins, uncles, and many of my friends, shoulder deep in the water, covered in blood.

Eventually, hundreds of whales are loaded onto lorries and driven the short three-minute drive, away from the black sand beach to the Harbour. All the dead whales get a number carved into them and get placed in rows, neatly sorted on the dock. We get our whale number and meet up at the dead whale where the number is carved in its skin, gathered around each whale are people having the same number as us. My grandpa starts carving slices of meat and blubber off the carcass, he hands it to my grandma, and she fills up the buckets and bowls, which then I carry to the car. On my way to the car, I see a few dead baby whales.

Empathy hits me hard, this should not make me sad, “be a man”, I tell myself, as I walk back for another filled bucket. School has been canceled tomorrow, everyone has been up late, and it will be a busy morning, salting and preserving the meat and blubber, we will salt everything, and place the meat and blubber into barrels. Then some of it will be dried, some frozen. We will eat it fried, cooked, and dried. Pilot-whale steak is my favorite meal.

That was the last time I partook in the Grind, barely a teenager. Today my stand on whale killing is considered a sacrilege to most of my countrymen, I think the tradition should be abolished. I remember how two Faroese guys joined the crew of the anti-whaling society Sea Shepherd, when they were there filming their Documentary series called “Viking Shores”, many years ago on the Faroe Islands. These two guys were shunned by everyone on the Faroe Islands pretty much. If I remember correctly, one of the two guys bailed on the show before they started recording, as the pressure from friends and family got to him. But the other guy went on with it.

I never saw the series but I often wonder what happened to that guy. Either way, there is, or was, zero tolerance for people who disagree with the whaling practice. And you basically get branded as an enemy of Faroese culture, if you do. The pilot whale slaughter is sustainable, and the killing of them is as compassionate as it can be. They live a free life, and are not hunted for sport, or raised in captivity, like most of the meat that ends up on our dining tables.

I think the meat industry, with its overfishing, and the mass production of animal protein for our diets is way out of control.

The symbolism of eating meat being heavily masculine is widespread. I have been strictly vegetarian for almost four years, and as a consumer, I have tried to only buy cruelty-free. I am not an activist, I remember where I came from, and know first-hand what sustainable living looks like. However, I have developed strong personal beliefs about being the cause of something dying, after a lifetime of struggling with how I felt about it. I would have never dared to tell my family I wanted to be a vegetarian, growing up. It would have been an insult to our way of life.

These narratives glimpse into my past, which I have woven into this essay. They should give an idea about the masculinity I looked up to as a kid and a young man. The gender roles in the Faroe Islands today, are not that different from what they are elsewhere in the modern Western world. We are slowly becoming more tolerant and inclusive, although there are still many more barriers to break down in regards to basic human rights.

A man like me: educated, straight, white, married, in his mid-30s, yet still in a way, still never felt like he fit in.

And for reasons that seem privileged – I never wanted to kill anything, and I felt embarrassed about it. I never wanted to show my emotions and avoided all conflicts. I eventually embraced and proudly wore many of the qualities I used to suppress, such as sensitivity, openness, and vulnerability. The next generation will have many parents with a view of the world like mine – challenging the stereotypes of so-called “real men”.

This contemporary view on masculinity is a result of the deconstruction of gender roles, pushed forward by gender equality movements in the last decades, and impacting how our kids are getting indoctrinated in childcare and by the educational system.

I spent most of my adult life feeling like my way of being a man was wrong, and that I was not a “real man”. I am glad to have reshaped my views on manliness.

I do not blame anyone for how I struggled with it while I was growing up, especially not my family and inner circle.

Go back a generation, in the same society as I come from, and try to think about how reversing the gender roles would have turned out. It would have worked perfectly. But no man would have freely agreed to take care of the home, if then the woman provided, by being the shepherd, fisherman, bird catcher, etc. There are obviously cases of the former, but only lightly sprinkled across Faroese history, and mostly only in the case of when the man of the house had seen an unfortunate fate.

I will leave you with a description of “The Faroese Woman”, Originally titled “Den færøiske kvinde”, published in the Norwegian Periodical “Husmoderen: Tidsskrift for hus og hjem” in 1904, p.312 (own translation from Norwegian to English). It was written by Sverre Patursson (b. 1871-1960), a very well-known figure in Faroese cultural history, as he was one of the first people to write prose in Faroese.

He was also notably the brother of Helena Patursson (1864 – 1916), the first woman to write a play and a cookbook in Faroese. She is proclaimed the first Faroese feminist and she was very politically active.

“While the male population of the Faroe Islands is distinguished by a fresh and core-healthy appearance, a resilient and elastic gait and posture, which is caused by the continuous journey across land and mountains, quite the opposite is in effect for the women, which are largely pale and emaciated, and even with a tired and sickly appearance, as if they are humans from a big city and not from the sea-surrounded storm swept Faroese archipelago.

Also in temperament, there is a difference. The men are – as usual islanders – quite lively, though on the bottom of their character, as with all people who live under strict and harsh conditions, exists a drag of familiar seriousness. The women, especially the young, are on the contrary excessively silent, quiet and modest. Even when they participate in our very evocative national dance, they almost never show liveliness in their performance. This difference between the male and female part of the population is so conspicuous that no stranger, who travels to our Islands, avoids noticing it… ” (Sverre Patursson 1904)

Be yourself, be a man, whatever that means to you.

A view from Norway: Feminism is history's most successful revolution

My Right to Exist

Queen psychosis tells all – A look into mental institutions

Queen psychosis tells all - A look into mental institutions

Read more about...