Table of Contents

“Can’t you just call it humanism instead? Or equality?”

Most people involved with feminism have at some point received “well-intentioned” questions from people who think the women’s movement is justified, but that we are ruining it for ourselves by calling it feminism.

These ideas can take root with the most convicted feminists. Is it really worth it? To insist on using this word? There’s no doubt that our lives would have been easier if we gave up this labour of Sisyphus by trying to cleanse the F-word of its associations with man-hating. Can’t we just find a new word?

No.

That so many people harbour prejudices against feminism – without bothering to understand what it’s really about – should not, strictly speaking, be the feminists’ problem.

It’s tempting to ask people to do a quick search on google before throwing themselves into the debate.

Alternatively, we can try explaining to these people that there’s nothing wrong with the terms humanism and equality, it’s just that feminism contains something more. Namely, the acknowledgement of how there are systematic differences in power, money and opportunities that are based on gender. Throughout history, the largest social group to have been oppressed and discriminated against, and for the longest time, has been women. Hence the word’s feminine ring.

In short, feminism is the name of the fight against gender discrimination. As a feminist, you do not want a person’s gender to limit their freedom or opportunities in this world. Simple as that.

The numerous misunderstandings over this are not due to feminists being unusually bad at explaining themselves and their project – they’re due to opponents of the women’s movement being successful in their centuries-old smear campaigns.

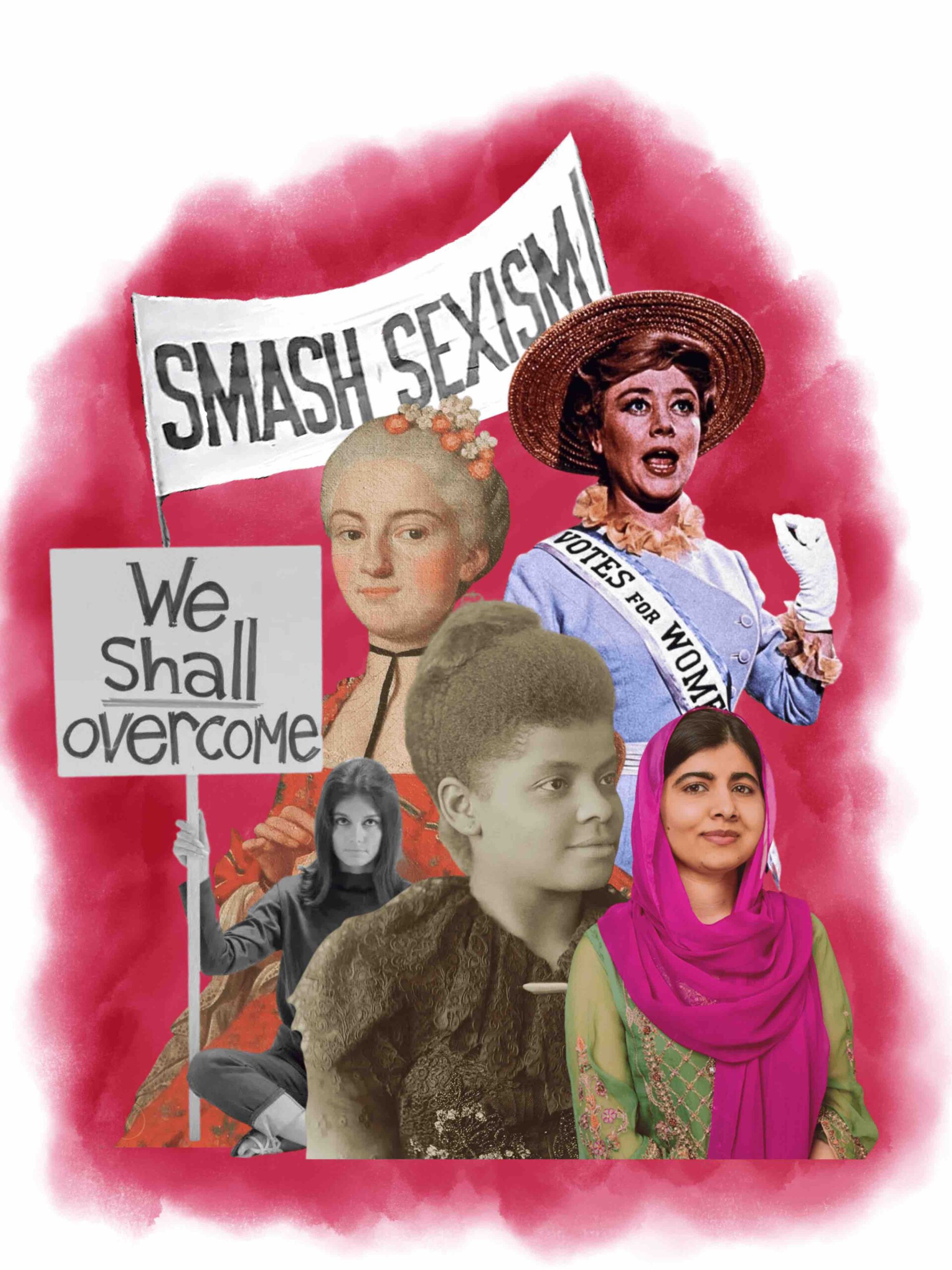

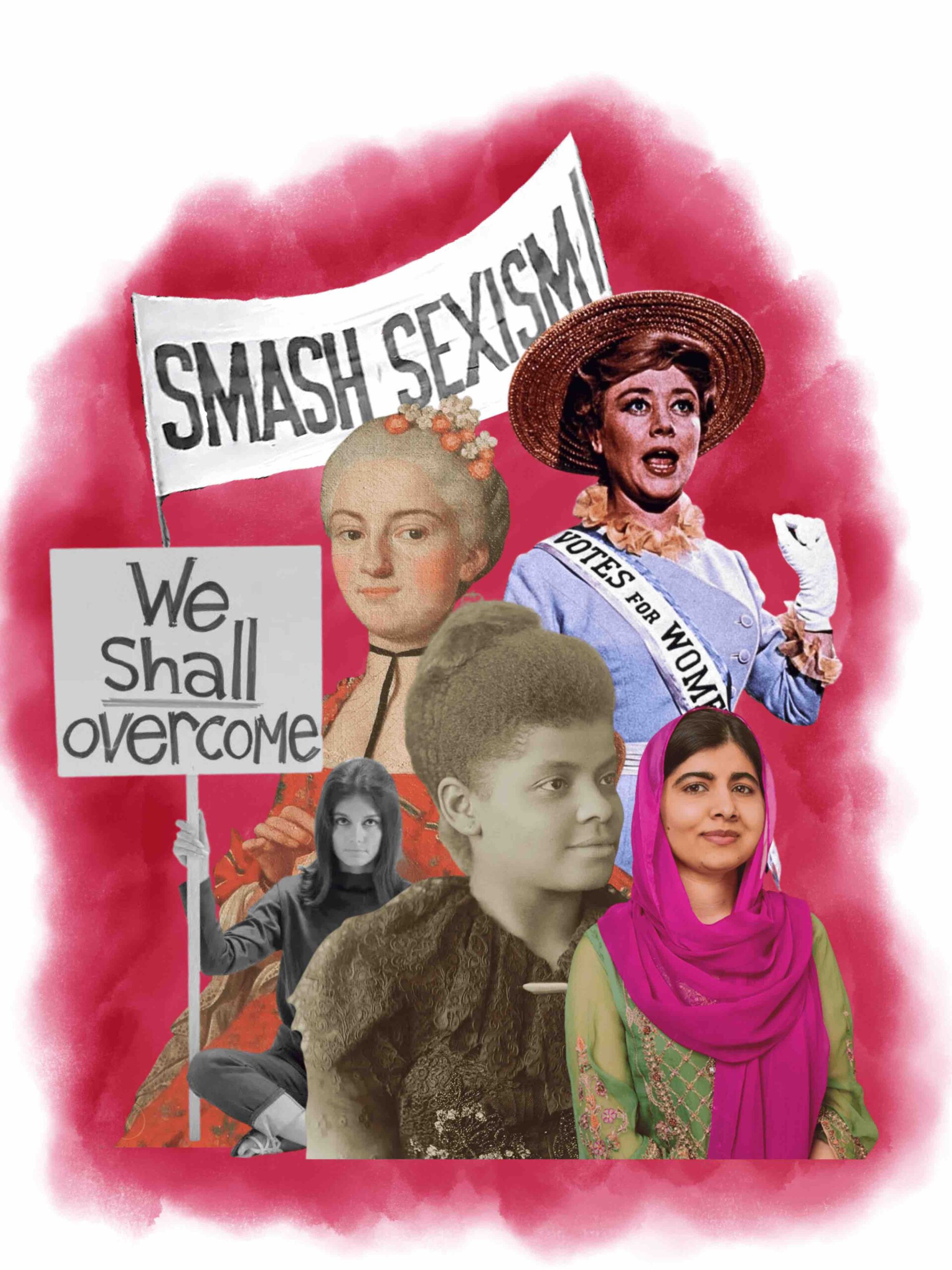

A short look at the history

Throughout history, feminists have been mocked and harassed, all over the world. In the Middle Ages, women who challenged authority were burned at the stake. In 18th century France, prominent feminists such as Olympe de Gouges, were executed by guillotine. During the 19th century, suffragettes were thrown in jail, while today feminists are imprisoned in countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia, convicted of removing their headscarves or fighting for women’s rights in other ways.

Feminists have been caricatured and ridiculed in the press, branded as grumpy, angry and unattractive; as frigid and as bad mothers. Sadly, many of these myths are still around today.

If you participate in today’s online debates about equality, you’ll recognize many of the characteristics mentioned above. The comments fields below any article on feminism clearly indicate that the battle is far from over.

Historically, feminism has been about modernization. The women’s movement has continually strived to adapt old norms, traditions and ways of thinking – and work out new ones, for modern times and modern people. Some will always oppose the breaking of traditions, but they normally lose in the long run. The world is rolling forward, slowly but surely.

Feminism can be described as history’s most successful revolution. Few movements have created such great social change in such a short time.

Little more than a hundred years ago, women were denied the right to education, to work, to divorce, and to vote in political elections. These things were reserved for men.

Thanks to the women of the first wave of feminists which emerged in the late 1800s, these fundamental rights were won in many countries. The next big feminist wave was in the 1960s and 70s involving feminists who had grown up in a society where most women were housewives. There were barely any kindergartens, and there were certainly no women’s shelters since no one then was talking about violence against women or sexual abuse in the home.

Abortion was illegal. Homosexuality was illegal. And there were hardly any female politicians. The women’s movement tackled all of these issues. The Scandinavian feminists of the 1970s fought for abortion laws, kindergartens and women’s shelters, and their efforts provided the next generation with far greater freedoms than they had experienced themselves.

These amazing results are not achieved by being polite or careful. The women’s struggle has largely been about forcing our way into the men’s world – be it working life, politics, sport, religion or art. The women at the front, kicking down the doors often do so at great personal cost. You’re unlikely to become popular by showing up at the party totally uninvited. The author Virginia Woolf pointed all this out in 1929, saying: “The history of men’s opposition to women’s emancipation is more interesting perhaps than the story of that emancipation itself.”

It was conservatives, who sought to ban women from being educated and earning their own money. It was conservatives who said no to women’s suffrage, no to female priests, no to pre-marital sex and no to gay rights.

So, to avoid ending up like some kind of no-person when history is being written, we have to be radical, open and curious. And never forget to listen to those younger than us.

Scandinavian feminism

Why are so many women still afraid of using the word “feminist”? I find that it’s often due to a misunderstanding. Many people think that feminism is a gender struggle, that one side will win and the other is destined to lose. As though freedom was like a cake for us to share, where more for you means less for me. But that’s completely wrong. The truth is we all win in a more equal society.

In the book The Spirit Level (2011), British social epidemiologists Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson write about the close link between a country’s economic and social equality and its levels of welfare. In short: Countries with small income gaps and a high level of equality between women and men, score consistently better on issues like health, well-being, life expectancy and economy. In other words, countries that maintain traditional gender roles lose out on several fronts.

The Nordic countries regularly top the lists of the world’s most egalitarian – and happy – people. Most recently in 2018 when the World Economic Forum compiled The Global Gender Gap Index, where the four top positions went to Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Finland. The basis for these types of accolades often focuses on the high numbers of women at work and our many good welfare schemes for maternal and parental leave.

In Norway, we have a gender equality law, a gender equality minister and a separate party dedicated to feminism. Right now, Scandinavian feminists have the wind in their sails: Every week, there are panel discussions, lectures, stand-up shows and festivals dedicated to feminism, in addition to a seemingly endless stream of articles, books, comics and blog posts about gender and gender equality.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that Scandinavian women are better feminists; or that all our problems regarding gender equality have been solved. They certainly haven’t. The idea behind this isn’t to force one recipe for feminism upon others, but because for decades we have been lucky enough to have the authorities on our side on a number of important issues. Women in Scandinavia live freer lives than many others, and since we have achieved so much, I believe we have a responsibility pass on our experiences beyond the Nordic region, while at the same time supporting those who find themselves sailing against the wind.

Because there’s a lot at stake right now. Recently we’ve seen authoritarian leaders seizing power in a number of countries, like Hungary, Poland, Turkey, the United States and Brazil. These offensive forces threaten freedom of speech, gay rights and women’s sovereignty over their own bodies. This means, among other things, that access to birth control is getting worse and that the possibility of having an abortion can become more difficult for many women.

It’s as though what these patriarchs are really dreaming about is a return to the days when “women were women and men were men.” In other words, a time when women stayed at home and were dependent on their husbands, and no one had heard of LGBTIQ. It is therefore more important than ever to remember that previous victories are not carved in stone and that hard-won rights can be lost again.

Show sisterly solidarity

Madeleine Albright, the former US Secretary of State, once said: “There’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.”

An absolutely terrible quote if you ask me, at least if you interpret it literally. Unfortunately, the belief that sisterly solidarity is about blind and unconditional support for any female activity has been increasing. Some dabble with feminism as though it were a cheeky little pink scarf to wear around your neck, viewing it as a career network to help each other to the top.

These women are not talking about overthrowing the patriarchate or overturning society’s power structures, they are talking about how to achieve personal success within that framework. But true sisterhood is not about applauding each other’s success or supporting women with values different to yours. It’s about being able to unite over important issues.

It’s not strange that many women are afraid of being seen as showing a lack of solidarity. Women have long been accused of it. “Women are their own worst enemies,” you could say, in that it’s quite typical for women to attack and ruin things for each other.

For example, if you criticize prostitution, some might accuse you of despising those who sell sex. Criticism of the porn industry is interpreted as an attack on women in porn films. “Not much sisterly solidarity around here, no!” Criticizing women’s magazines can be seen as looking down on other women’s interests. If you criticize the media’s beauty ideals, it can be spun that you’re just envious of the models. “Typical girls. They can’t stand other women showing how beautiful they are!”

This is how women’s opinions are trivialized. By accusing them of having a personal and immature agenda, thereby reducing any engagement they have to a matter of rivalry. It is important that we recognize and expose this type of domination technique. Women should of course have just as much freedom to disagree with each other as men.

Scandinavian feminists are often accused of not showing any sisterly solidarity with minority women. “Feminists have failed Muslim women”, and “These self-absorbed, white, middle-class, women just complain about their own luxury problems.” This sort of criticism has come regularly, for many decades:

It is true that the women’s movement in Scandinavia has been characterized by white women and their issues. Fortunately, the feminist community is becoming more diverse, and over the past decade, a large number of women from minority backgrounds have joined the debate.

These women often have far more to lose from going out in public than others, and we regularly hear of women that have been frozen out, harassed or threatened after speaking out in the media.

They have been assaulted in the street, some live with attack alarms and police protection, while others say that their vulnerable situation has given them mental health problems. Nevertheless, we are seeing a stream of courageous, minority voices participating in social debate; and their agenda includes the fight against honour culture, forced marriage, genital mutilation and, not least, racism.

Among these new activists, there is a movement called “The Shameless Girls” which emerged in Norway in 2016. The Shameless Girls started with three young women – Nancy Hertz, Sofia Srour and Amina Bile – who wrote several newspaper articles about how tired they were of their brothers having more freedom than them. They used the term “social control” to describe how many young girls are being restrained in their own communities. It might be a little reminder that people are “keeping an eye on what you’re doing,” perhaps a taxi driver hinting at how you’re out a bit late that night, or your brother’s friend saying that you’re showing too much skin. An internal, tell-tale culture – moral policing, in other words.

“Enough is enough,” said the young women, with the message: “We will not carry on being ashamed of living ordinary lives. We refuse to be the measure of our families’ honour.”

The shameless girls hit a current nerve, becoming role models for an entire generation; and for several years they have travelled all over, discussing this theme with teenagers, parents and politicians.

Even though many women from minority backgrounds have joined the fight against social control in recent years, it does not mean there is agreement on where the problem lies or what measures are needed. We’re talking about individuals of course, not a homogenous political group; something an increasing number of women from minority backgrounds are keen to point out: We are not just one vulnerable group of oppressed victims needing to be freed. To be treated as an individual – with all the complexity this entails – is quite simply a privilege, that not everybody is granted.

Unfortunately, those who regularly criticize feminists for behaving cowardly in the debate about minority communities often have an agenda.

Because when they say you are “failing minority women” what they really mean is that you should be more critical of Muslims and Islam. They would like you to participate in a form of criticism of Islam that paints with too broad a broad brush to make any real point: “Islam is hostile to women!”, “Hijabs are oppressive to women!”, “We have to stop immigration, now!” Exclamation mark and period.

It’s natural that many women refuse to join the debate when these are the premises. Racists and those opposed to immigration cannot be allowed to misuse feminism for their self-proclaimed culture war.

At the same time, it’s very important that feminists loudly support the many voices striving for change within their own religious communities. For example, there are a number of Muslim feminists who have attracted attention by interpreting the Qur’an in new ways.

In recent years, we have also heard about female imams who have stood up to contradict conservative Islam. Such as, the French imam Kahina Bahloul, who has made the modernization of Islam a key issue. She believes that Muslim women and men should have equal rights, telling French news channel France 24: “The major problem with Islam today is that it is viewed through the lens of a man whose understanding of society is patriarchal, if not misogynist. We should be able to approach religious texts differently in the 21st century.”

There’s no doubt that very much of the discrimination women face worldwide is rooted in religion. For centuries, religious texts have been used as justification for denying women their freedom.

In Scandinavia, religion no longer plays a dominant role in politics or society, which is an important prerequisite for gender equality. Many hard struggles lie behind us – battles to allow cohabitation outside marriage, to allow female priests, and gay marriage. Resistance to these issues was for a long time far too great for there to be any breakthrough over these demands.

But because of the church’s own women and men – who joined the struggle from within, and didn’t give up – we now have a far more generous Christian culture. Today, for example, gays and lesbians can get married in a church, in all the Nordic countries, and in Norway, the majority of bishops are in fact, women.

In recent years, there have been several public debates over various Muslim practices, such as the wearing of hijabs at school, the ban on handshaking with the opposite sex, and gender-segregated swimming lessons in Norway. Many people are keen to show respect and understanding of religious customs and therefore go to great lengths to accommodate the wishes of the Muslim communities. But it’s important to remain cool-headed here, and not forget our principles; like how school should remain secular. Children should not wear religious clothing that prevents them from playing and expressing themselves. And we abolished gender-segregated teaching 50 years ago.

In many parts of the world, we no longer measure a woman’s value in terms of honour and shame, and we will never go back. If we accept the wants and needs of the most conservative forces within minority communities, we will fail all those who actually want to change these practices from within: Women and men who have already sacrificed a great deal in the struggle to gain the same freedoms we enjoy.

We all have to stand up to male-dominated honour and shame culture. Today, these terms are almost exclusively linked with Islamic culture and upbringing, although “shame” and “honour” have been the mainstays of patriarchal culture throughout history. These expressions are quite simply devices for controlling women’s sexuality.

The concept of internalization

A few years ago, I watched the American TV series Breaking Bad, and I remember while watching it that I was annoyed by the female character, Skyler. I was annoyed at how she constantly gave her husband Walter White “the silent treatment,” using silence to indicate that she was pissed at him. What incredibly annoying behaviour!

I wasn’t so bothered by Walter White turning into a ruthless drug producer who took the lives of innocent people – not even remotely. I kept giving him new chances because I knew he was actually a good man deep down. I’ve granted the same generous forgiveness to criminal gang bosses like Stringer Bell, serial killers like Dexter and sociopaths like Ray Donovan. But silent Skyler – what a bitch!

By the way, I was not alone in disliking Skyler – the character was so unpopular among fans of the series they set up their own online hate forum, especially for her. But the fact of the matter is this:

We all react more negatively to an “unappealing” woman than to an “unappealing” man. Both women and men are a little more sceptical of women.

We are continually getting new reports and study results showing that we operate with different ethical codes for each gender. For example, a survey carried out by the Norwegian think-tank Agenda found that the country’s students were more critical of career women than of career men. The information provided about them was completely identical, however, the woman was considered less sympathetic, more selfish, and a poorer parent than the man.

Similar studies have shown similar results in many other countries and spanning many decades. Being successful at work increases a man’s chances of being well-liked, while the opposite is true for women: A woman’s chances of being liked by others lessen the higher she goes in the hierarchy. At the same time, it turns out that both men and women expect more care and empathy from their female bosses.

So, these attitudes are supported by both genders; we have internalized them. The concept of internalization, in this case, refers to how women themselves adopt society’s views on women. We are evaluating ourselves, and our fellow sisters, with the same patriarchal gaze. It’s no wonder these mechanisms appear, and I don’t think any of us – no matter how feminist-oriented you are – fully escape these inner voices.

It is important we realize this, and don’t go around thinking of ourselves as free of sexist or racist impulses. We too would then be part of the problem. If someone alerts you to your own prejudice; don’t go on the defensive. Instead, listen to what’s being said, examine your own attitudes, and work on yourself.

Because it’s not like women are born with an inherent ability to challenge authority; one that enables us to see through the systems and structures. Women can be complicit in sustaining patriarchy, just as men can support the fight for equality. To be a feminist is to take a step back and try to see the system – and oneself – from the outside.

Again, language can help us along the way. These mechanisms are far easier to spot if we have a language that describes them. Over the last few decades, feminist theorists have coined a number of new words and concepts that can help us see ourselves from the outside. For example, it could be the term “the binary gender system,” which describes our traditional bisexual model.

In recent years, most people have come to realize that there are people who define themselves outside this model; not everyone feels that they are one hundred per cent male or one hundred per cent female. Some feel that gender only defines them to a small degree, some feel that they are born in the “wrong body,” while others again consider gender to be fluid. So, with an expression like “the binary gender system,” we have found a term for something we didn’t previously know we needed one for, namely the idea that there are only two clearly defined genders.

“Cis-person” is a term that functions similarly. It basically means that you are not trans. Why in the world do we need a word for it, some are of course wondering. But again, we’re talking about a word that can help the majority recognize their own privileges. For example, personally, I never get funny looks when I enter the women’s toilet, I am never harassed for wearing makeup and have never experienced invasive questions about my sexual identity or my genitals. These are my cis-privileges. Those who face all this regularly of course need a language that enables them to talk about it.

Some view this linguistic development as an excessive form of political correctness and voice their disapproval.

That’s how it is with these new words: When someone points to you and says you live a “heteronormative” life, they’re most likely applying words to a part of your identity that you haven’t reflected on before. You feel categorized and pigeonholed, perhaps for the very first time. This can make many people feel defensive.

Since the inhabitants of the Nordic countries are among the world’s most privileged, we should also be those most capable of recognizing our own privileges. But unfortunately, that’s not the case.

From the book “Hvordan bli (en Skandinavisk) feminist” by Marta Breen

Do you support Vía?

Vía counts on your support. By subscribing to Vía you contribute to the future of a medium that specializes in, and puts emphasis on equality and diversity.

Vía, formerly known as Flóra, was founded 4 years ago for critical readers that want to dive underneath the superficial layer of social discussion and see it from an equality, inclusion, and diversity perspective.

From the beginning, Vía has covered urgent societal topics and published issues and articles that have shone a light on inequality, prejudice, and violence that exist in all layers of society.

We emphasize publishing stories from people with lived experiences of marginalization.

Every contribution, big and small, enables us to continually produce content aimed to educate and shine a light on hidden inequalities in society, and is essential for our continuing work.

Support Vía

A love letter to burlesque and my fat body

My Right to Exist

Equality and innovation – Just consulting

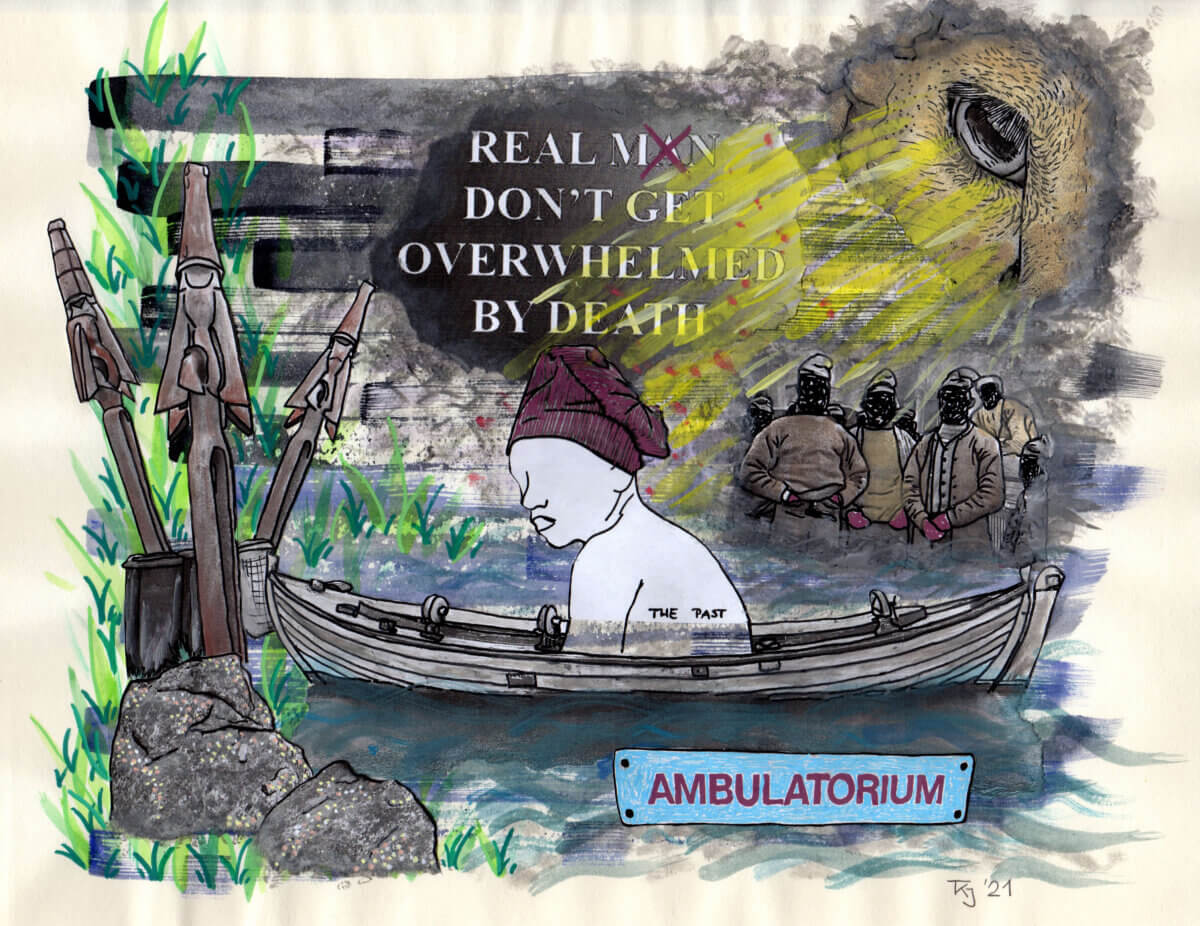

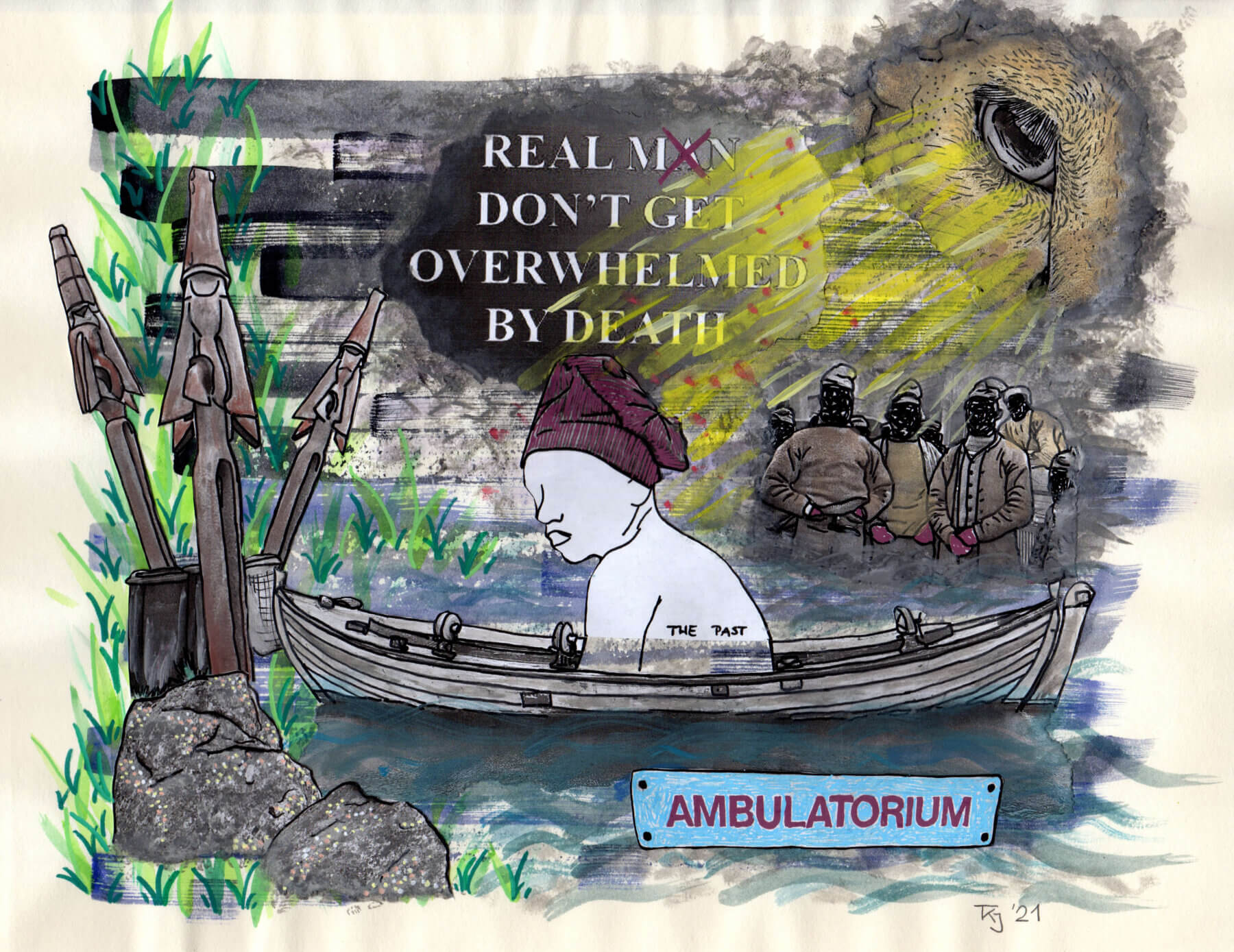

Be yourself, be a man - How to be a man in the Faroe Islands

Read more about...