Inga Björk Margrétar Bjarnadóttir

@ingabbjarna

@ingabbjarna

images:

Heiðdís Buzgò

@HeiddisBuzgo

translation:

Elinóra Guðmundsdóttir

Every person with a uterus will at one point or another, be faced with the duty of getting screened for cervical cancer. It’s stressful and definitely not the most exciting mission, but nonetheless very important. When you are disabled with a uterus, the stress of this upcoming event increases. Is it accessible? How does this take place? Somedisabled bodies are unique, different than what we are used to, and have experienced a lot of pain and prejudice when seeking healthcare. It’s therefore normal to think of cervical cancer screening as a frightening experience?. My experience of cancer screening was, to tell the truth, traumatizing. There were no mobility aids available to get on the examination bench, accessibility was poor and I got the feeling that no one with a physical disability had ever been in that room before me. I had, as so many times before, to instruct, guide and educate in a situation where we all just want to feel in the safe hands of healthcare professionals. After the experience, my thoughts were with the many other disabled women, especially the ones that are more marginalized than me. Women that are considered less worthy in society and don’t have support, assistance and access to education, for example women with intellectual disabilities or women with multiple disabilities. It would not surprise me if disabled women are less likely to show up for cancer screening, but statistics on the matter do not exist to my knowledge.

This is not a unique example. Time and time again I’m surprised by how inaccessible and prejudiced the Icelandic healthcare system is. My experience of using a wheelchair for the majority of my life, conversations with my disabled and chronically ill friends, and now at my new workplace Þroskahjálp (e. National Association of Intellectual Disabilities).

Stories of serious illnesses that were diagnosed way too late, stories of prejudice, aggression and abuse.

Researches have shown that the life expectancy of people with intellectual disabilities is less than abled people. That is a bleak fact. Research from the UK shows that people with intellectual disability live on average 16 years shorter than their fellow compatriots, and even though that in some cases we can assume that people with intellectual disabilities may also be in poorer physical health, it’s also clear that this group in society receives poorer quality of healthcare which leads to untimely deaths (Pauline Heslop, 2013). At Þroskahjálp’s seminar on mental health and addiction among people with intellectual and related disabilities last year, it came clearthat health services in Iceland for this group in our society are far from acceptable. Psychiatrist Dagur Bjarnason stated that researches show that the risk of death from breast cancer is doubled, that there’s an increased risk of diabetes and cancer, and that depression and anxiety are left untreated. Furthermore, there is evidence of over-treatment in other respects, that is, people are given antidepressants in order to deal with behavioral challenges.

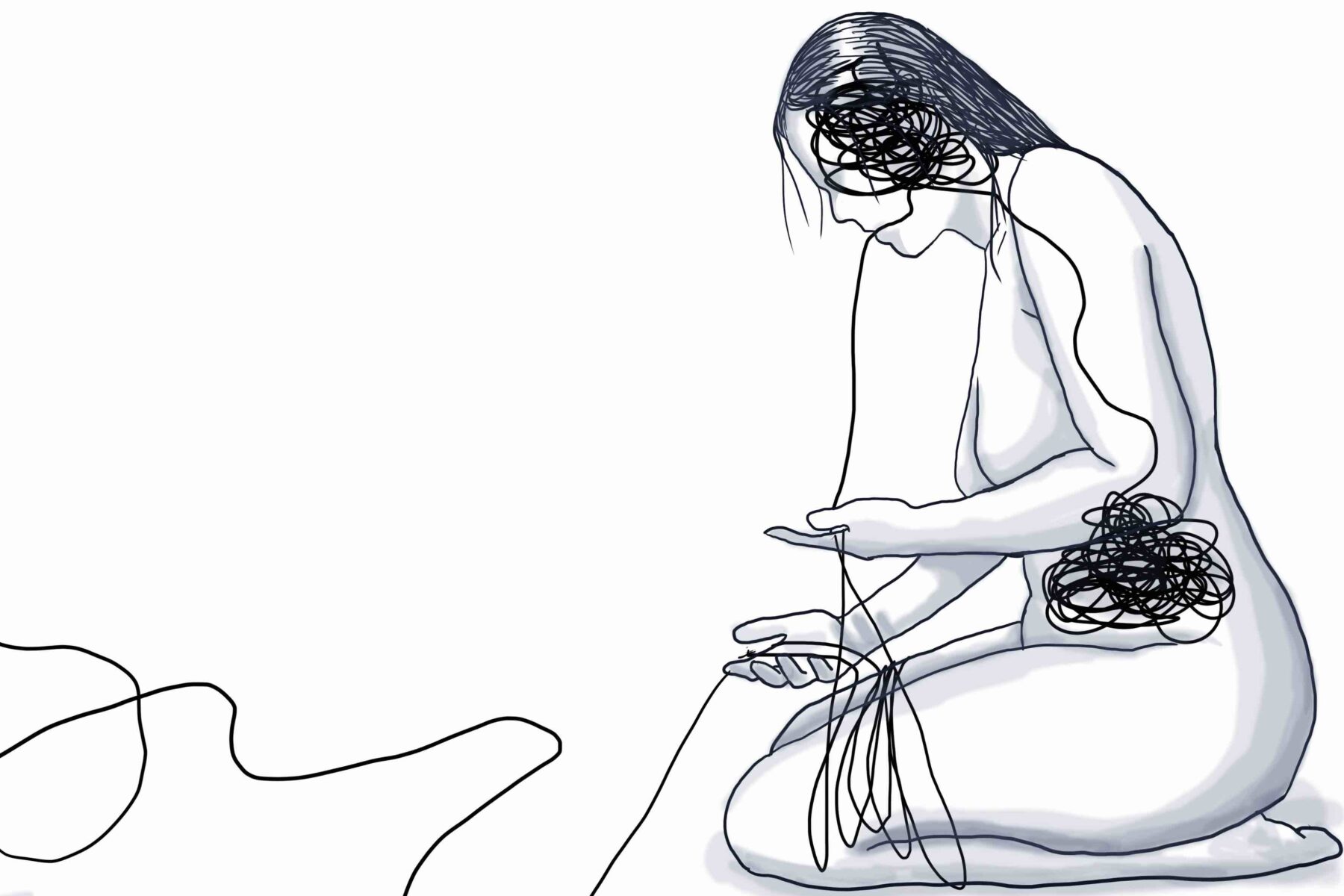

Disabled people’s distrust towards the healthcare system is not a surprise. The attitude which is called the medical approach to the concept of disability still prevails in our society. In the medical approach disabled people are seen as subjects that need fixing, correcting and improving, implementing the idea that the person is unworthy and defective. The fight to have the concept of disability approached as a social issue has been ongoing for the past few decades, meaning that the obstacles that a disabled person faces is not their personal problem, but the society’s problem. It’s the society that needs to adapt to existing diversity, not the individual that needs to adapt or be excluded from the society. That disability is a part of the precious diversity in society.

Our healthcare system has taken a few important steps, but we still have a long way to go.

We need to improve the education for healthcare professionals about the rights of disabled people, we need better accessibility and to increase the mobility aids available so that disabled people can undergo treatments and screenings just like other people. Proactive healthcare needs to be available, including home visits by healthcare professionals regardless if people live in private homes or use residential services.

It’s hard on many people to make appointments, wait in crowded waiting rooms, follow up on their cases and even realize that they need health care in the first place. Furthermore, we need to believe disabled people when they seek health care, and not to dismiss all their issues and pain on previous diagnoses.

Disabled people have the right to good health and wellbeing, and that healthcare professionals take good care of them. Just like everyone else.

Do you support Vía?

Vía counts on your support. By subscribing to Vía you contribute to the future of a medium that specializes in, and puts emphasis on equality and diversity.

Vía, formerly known as Flóra, was founded 4 years ago for critical readers that want to dive underneath the superficial layer of social discussion and see it from an equality, inclusion, and diversity perspective.

From the beginning, Vía has covered urgent societal topics and published issues and articles that have shone a light on inequality, prejudice, and violence that exist in all layers of society.

We emphasize publishing stories from people with lived experiences of marginalization.

Every contribution, big and small, enables us to continually produce content aimed to educate and shine a light on hidden inequalities in society, and is essential for our continuing work.

Support Vía

Thirty-nine people died from suicide

My Right to Exist

Forréttindapésar: Ekki biðja mig að vinna vinnuna þína

ADHD: Harmful Stereotypes and Invisible Girls

Read more about...