Steinunn Ólína Hafliðadóttir

translation:

About a year has passed since the founding of FLÆÐI art gallery. During this one year countless exhibitions have been held at its space, which despite of a short run time has had to be relocated a few times. Today FLÆÐI is situated in a bright space at Vesturgata 17, where new exhibitions are put up weekly. Antonía Bergþórsdóttir, Brynja Kristinsdóttir, Dorothea Olesen and Íris María Leifsdóttir now run the gallery, and ever since the first opening they have put emphasis on creating an accessible space for artists, especially immigrants and other minorities, who in their opinion have not been provided equal access to the art scene as others.

What makes a space like FLÆÐI more accessible than others?

Antonía: Im my opinion FLÆÐI is a more accessible space because artists don’t have to pay a fee to exhibit their work. The cost of exhibiting can often be an obstacle for young up-and-coming artists who want to show their work. Furthermore, young artists aren’t necessarily given the opportunity to hold exhibitions unless they are students of an art-related field.

Dorothea: Exactly, and many artists don’t have a wealthy background, which often seems to be essential if they want to exhibit.

Antonía: … or a network of people, which is often a deciding factor in whether or not an artist manages to make a connection to the art world. In our opinion it is also important to create accessibility through advertising. When we at FLÆÐI put up an ad for an open space, we make sure it is also written in English. What we want is to reach groups that don’t necessarily have Icelandic as their native language, and that matters. We have also focused on a target audience in the suburbs by paying for advertisement that reaches those areas. I especially remember the first woman who had an exhibition at FLÆÐI on Grettisgata, when that was our location. Her name is Joanna Kedzierska and she is from Poland and had lived in Iceland for three years; she was a very big name in Poland but had yet to print her works in Iceland whereas she was unsure they would sell. Furthermore she didn’t have any connection into the Icelandic art scene. Nevertheless, she saw our advertisement, decided to go for it and her show at FLÆÐI was a great success. I remember she got quite emotional. She was grateful for the opportunity; said she’d never encountered such an accessible exhibition space. I think that sheds light on the big role language plays in creating accessibility; had we not put up advertisement in English it is very unlikely that this artist would have went for it.

Dorothea: We offer the possibility of holding a solo exhibition, which is not a given thing. We have also offered artists help with putting up their show. Of course, each person that comes in has different experiences and knowledge; some come in with a concrete idea of what they want to do with the exhibition but others might not have tried to put up an exhibition before. At least I think it’s nice that we can provide this sort of service and thereby assist artists in becoming more visible.

Antonía: We try controlling the artists as little as possible. Preferably we want everyone to be free to tell their story through the positioning of their work.

Íris: It is so important that artists get the opportunity to convey their message at their exhibitions. And FLÆÐI wants to provide a space for that sort of thing.

Dorothea: That way, people who come to us can be sure that they are stepping into the world of a specific artist when entering FLÆÐI.

Have you had a good reception?

Antonía: Yes, it has been going great and we’ve gotten a good reception. I also think it is pleasant to see women being the majority of applicants who want to exhibit at FLÆÐI. It’s also interesting because the art world in Icelands tends to be male-dominated. Especially among painters.

Dorothea: Not just in Iceland but also throughout history. Men have received a larger space in the art world, and the system often seems like it was created around them. It seems easier for men to get recognition in the art world as well as access to exhibition spaces. Of course there have been big changes throughout the years but traces of this male-dominated system remain. That is why it is important to try to maintain this continuing change which aims at giving members of every group space within the art world. Commonly it is more challenging for women to get themselves known and that is why it is important to have a space like FLÆÐI which welcomes everyone.

Antonía: Personally, I feel like women are expected to follow more “rules” than men when it comes to art. Women’s art can’t be too cliché, or it can’t be this or that; it would be lame to just paint a picture of a flower, while men are usually given more freedom in choosing a subject.

Íris: Yes, they seem to have more room for mistakes.

Antonía: Much more flexibility. I’ve often heard from women who have exhibited at FLÆÐI that they would never dare to show a piece that was still in progress.

Dorothea: Perhaps women are more often self-critical and take fewer risks; simply because their fall will be greater if their art gets a poor reception? FLÆÐI’s policy has never been directed exclusively at women but at the same time it is interesting to see how many women apply for exhibiting compared to men. It sends a certain message in my opinion. It sheds light on the fact that opportunities for women and other minorities are lacking.

What kind of art is exhibited at FLÆÐI?

Antonía: It’s very interdisciplinary. We’ve had everything from performance art to paintings and ceramics.

Íris: And we have had all sorts of applications; book and music publishings, yoga, meditation and healing.

Dorothea: And OK, with that I want to say; and I might be extremely biased because of this disgusting BA thesis I’m working on, but I’ve been thinking about gender in the art world for a while now and I think there is something to the idea that women’s works are much more personal in general and display some inner self-examination; a personal experience.

Íris: Art is, of course, very expressive.

Dorothea: Yes, of course it comes with some self-examination that I find more visible in the works of women than men.

Are women received differently than men in the art world?

Antonía: I personally think women are expected to prove their works to be meaningful so that they can advance. As if their works can’t just be art but rather that they need to be intertwined with some negative feminine life experience.

Dorothea: And this self-examination I mentioned is derived from somewhere, we are trying to interpret our experience; what it’s like to be a woman in society. And through art we can touch on subjects that never get as much value as they should.

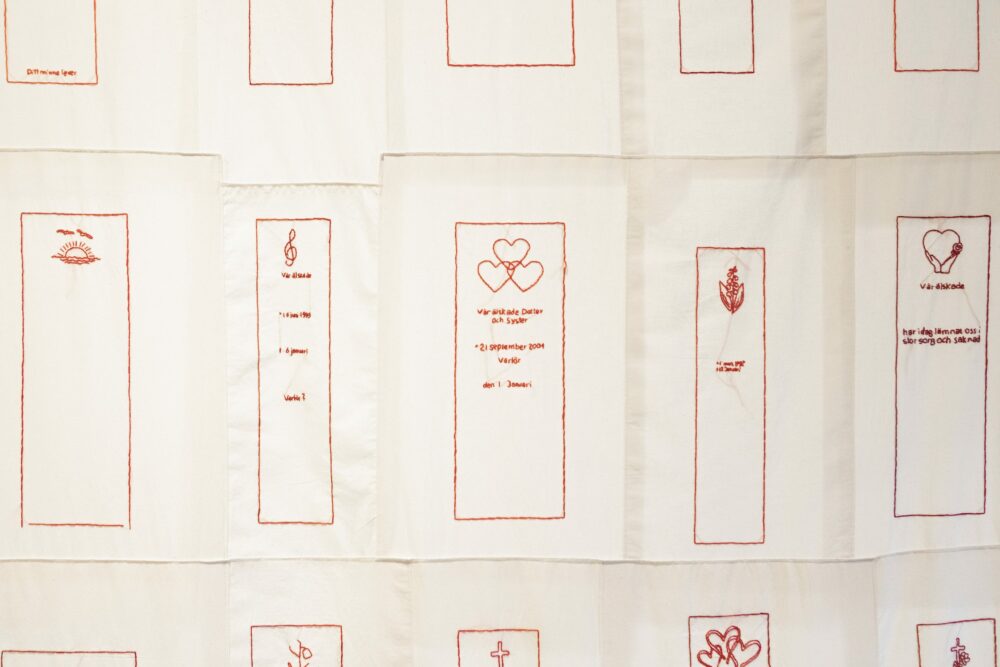

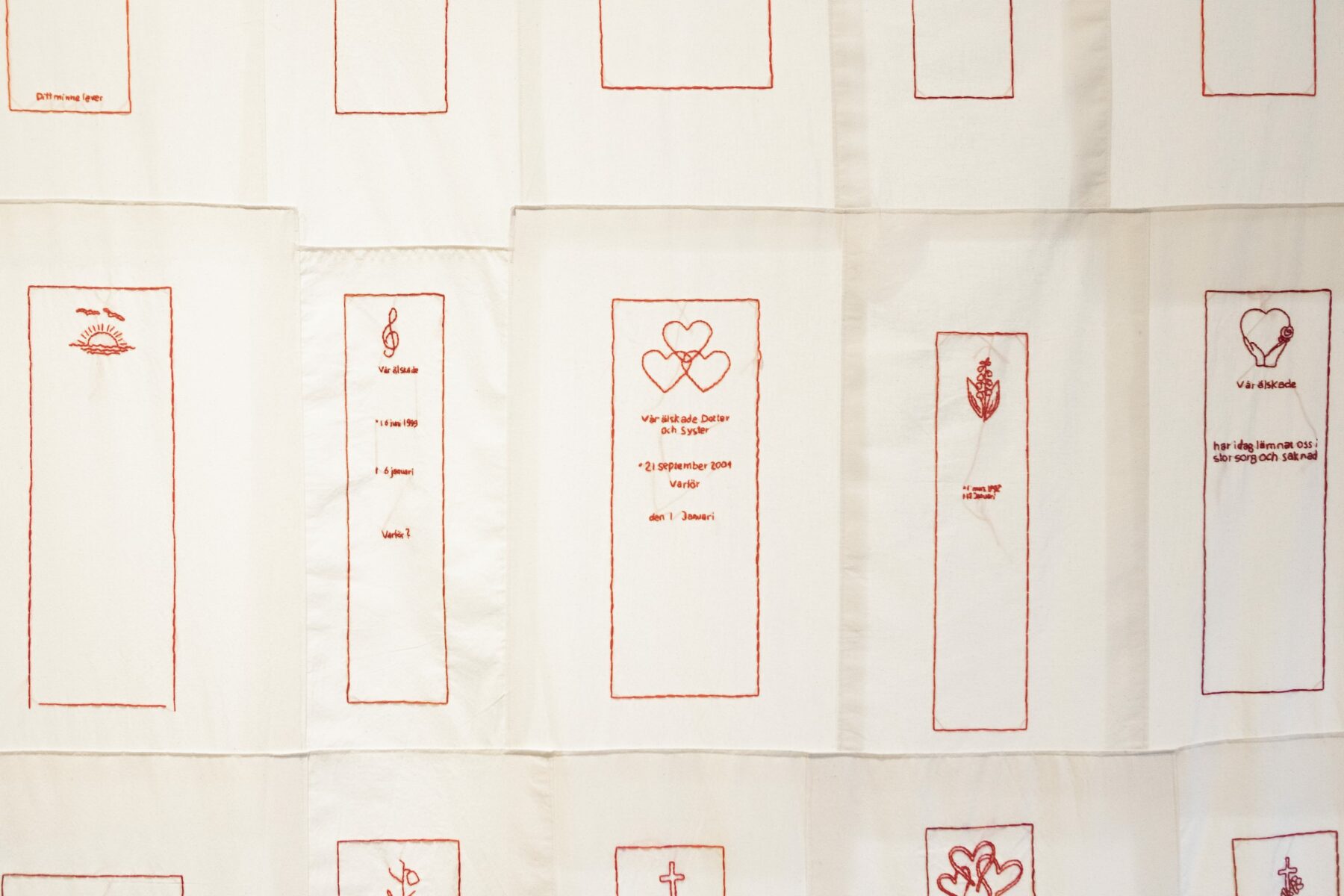

Íris: This resonates with me. I opened up about an abortion I had at an exhibition I held at FLÆÐI last year. That exhibition was very important to me; it is so important to me to be able to express myself through art. It brings a certain calm, a certain tranquillity; but it is also always good to be able to tell your story and especially in such a safe space like FLÆÐI. Exhibiting your art always comes with vulnerability; you expose yourself with it and show what’s on your mind.

Antonía: Yes, the art is always very close to your heart. Creation is so closely related to the creator’s state of mind when it happens. In that way, each exhibition can be a reflection of the state of mind you were in each time. That’s why it is important to give access to all sorts of people; that way we can get to know different people as well as put ourselves in their shoes.

Are you affected by this masculine bias in your work?

Antonía: Well, I think FLÆÐI would be received differently if we were four men; especially when it comes to donations and access to institutions. That is just my personal opinion, I think today’s art world is particularly supportive towards young men who are taking their first steps in the art world.

Dorothea: And not just in fine arts but also in the music business for example. Although it is clear that people now aren’t as tolerant towards that sort of bias as they were. We can see an example of that in recent criticism of Keiluhöllin, where it was decided to book an all-male line-up for some concert they were having. Of course it is easy to say Keiluhöllin didn’t set out to invite only men to partake but either way this selection sheds light on how men taking up space is the default. Men seem less hesitant to just go for it and get themselves known, which sucks to say because I don’t want people to interpret it in a way that I think women are in some way weaker than men. It’s more about how society has laid things out. Girls aren’t encouraged as frequently to be loud or to go into entrepreneurial work compared to boys. Luckily, society is mostly going against this norm but that doesn’t change the fact that there is a systemic standard which unconsciously affects girls in this regard. I feel it strongly and have felt it, without necessarily always knowing why.

Antonía: I’ve heard this from many women and I do feel it myself. I often feel like I’m not allowed to be emotional or loud without being labelled a brat or a diva; being too much. And I mean, if men showed the same behaviour it would most likely be accepted as an aspect of their personality. It is like “professionalism” should be characterised by lack of emotion.

Dorothea: And then there is the question; is this the sort of society we want to live in? Where we can’t express our feelings? And now I speak for everyone. Why do we think lack of emotion is a sign of strength?

So you put emphasis giving lesser heard voices their chance to speak?

Íris: Yes we are confident in that and that thought absolutely shapes FLÆÐI. We want to show marginalised groups in a clearer light and create opportunities for a more diverse group of people to express their stories and emotions.

Antonía: Which is just so great. The space at FLÆÐI completely transforms between exhibitions because diverse individuals can come in there and be free to do as they please. The building at Vesturgata has more artistic possibilities than our previous ones. We have a small movie theatre in the space which can be used for showing sound or video art. Then there is also a bright space which is suitable for artwork, performances or other events.

Íris: We want to be well informed on current affairs in our community. Art reflects what is happening in a modern society. We have had exhibitions that are focused on emotion in the time of Covid-19 and we also had a queer exhibition during Pride and one that touched on domestic violence. In that way art exhibitions can show what is happening in our society and how people experience it.

Dorothea: I guess FLÆÐI is also about that; giving others a chance to be heard. FLÆÐI is about creating a safe space and an area for people to express themselves. About creating that freedom of expression that people get where? On Facebook? Twitter?

What’s next at FLÆÐI?

Dorothea: Of course it would be amazing if we could get housing that is just FLÆÐI forever. FLÆÐI is a non-profit organisation; there is no monetary gain in what we do. I don’t know if it is simply because people don’t realise how incredibly valuable art and culture is.

Íris: What we do is all volunteer work and we have relied on the volunteering of people who are ready to lend a hand and even help us find housing.

Antonía: Until now we have used spaces that are privately owned. But then it is just a matter of time before the private owner demands some payment. For this reason it would be preferable to find some government owned space that isn’t being used.

Dorothea: Of course it would be best if The City of Reykjavík would support us; the city should be interested in having a place like FLÆÐI. It is important to support the art and culture scene, especially at times like these. It is important that we stand together in increasing artist’s visibility.

— — —

Get to know more about FLÆÐI at their website or at Instagram and Facebook. It is also possible to be in contact via e-mail at info@flaedi.com.

COVID-19 as a Feminist Matter

My Right to Exist

Making Space for Women and Non-Binary in the (Danish) Art World

Recycle till you drop

Read more about...