* TW *

This article covers the history of disabled people back to the ’50s. To accurately tell that history some terms have been used in the direct quotes in this article that might be very triggering.

Table of Contents

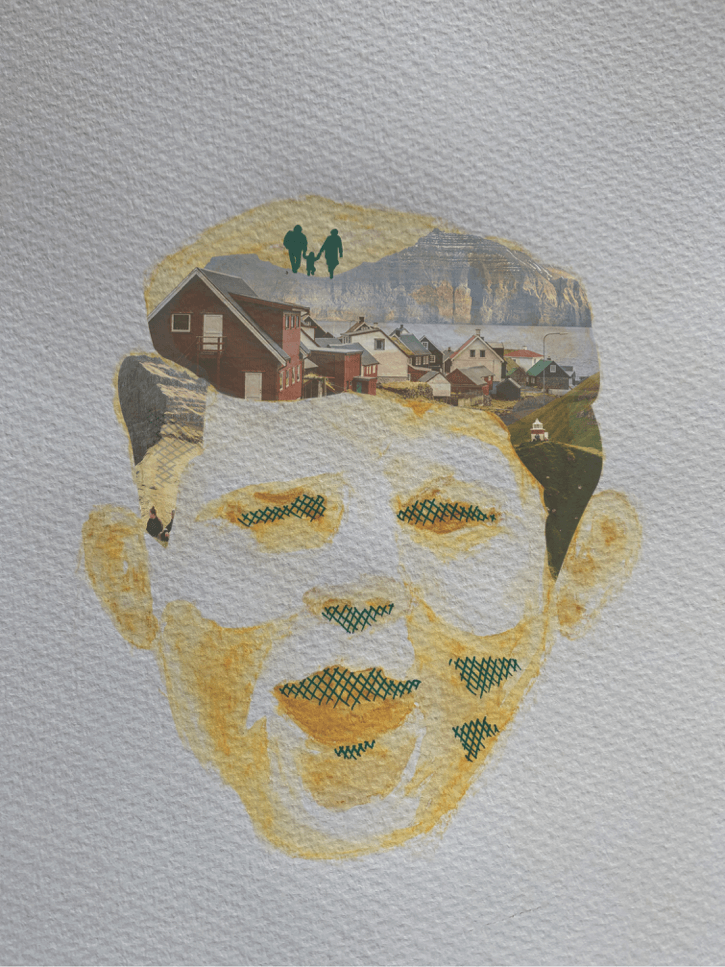

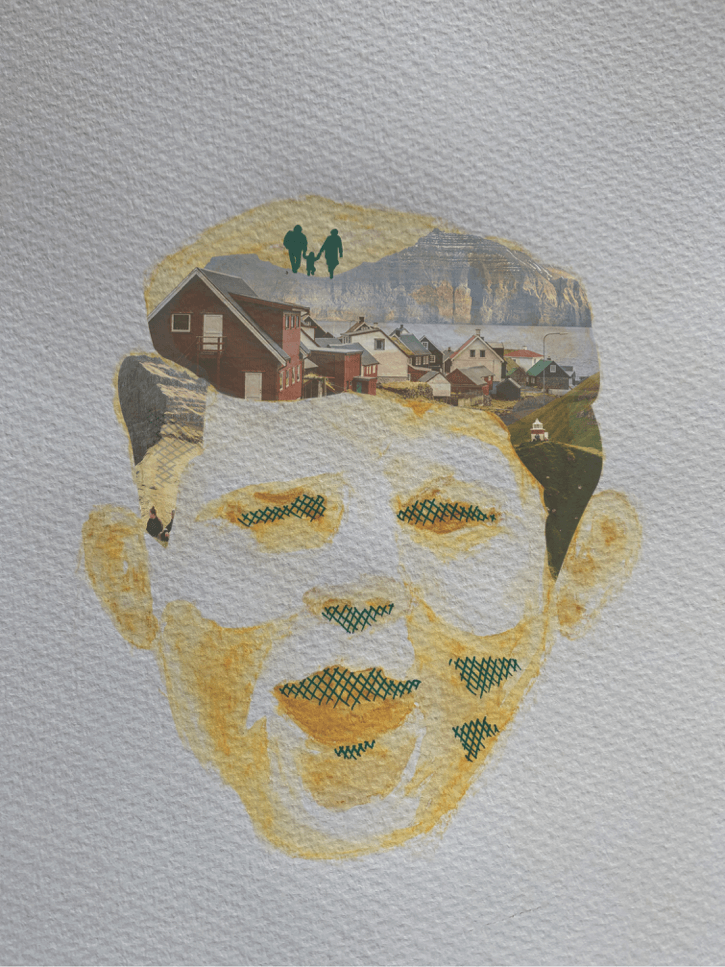

Disability in Greenland and the Faroe Islands

During the 20th century, hundreds of children and adults with disabilities from Greenland and the Faroe Islands left their homes. On the advice of doctors, social workers or local authorities, because their families were overwhelmed with caring for them or because there were no suitable local support services, more and more disabled Greenlanders and Faroese embarked on ships to cross the sea to faraway Denmark. Upon arrival, their new lives in many ways resembled a different world – with a foreign language and culture, and the strict procedures and rules in the special institutions where most of them were accommodated. That is, until their left-behind families began to resist.

The forgotten in society

“And are we just going to keep sending people off to Denmark, where every institution is filled to the brim? We should have come so far in 1971 that we can shoulder the responsibility for our own people. The right thing to do would be for the parents to get together. In our neighbouring countries, it seems that it really is the parents’ associations that are acting, that are actually doing something.”

If you had opened the Faroese newspaper Dagblaðið on the 6th March 1971, you might have come across Helena Samuelsen’s article on disability with its provocatively asking title The forgotten in society? (fo. Tey gloymdu i samfelagnum?) Samuelsen, herself the mother of a child with an intellectual disability, critically pointed out the ways in which local authorities, but also the Faroese society as a whole, had let down their fellow citizens, and that within the span of just a few decades, the majority of disabled Faroese had been sent to Denmark. As a result, she concluded, they had all but disappeared from public life in the small island communities.

In Greenland, the systematic placement of people with disabilities in Danish institutions had been even more thorough, with some people scathingly stating that the country was virtually “vacuum-cleaned” of disabilities.

That parents found it necessary to send their children to overcrowded institutions in distant Denmark and into the hands of strangers, without certainty of their welfare or when – if ever – to see them again, seems unthinkable to us today. So what were their reasons for taking this drastic step? A look at the local conditions in Greenland and the Faroe Islands during that time gives us some clues: for one, neither of the regions had any specialized care or rehabilitation, education or housing facilities for people with disabilities. On the other hand, the Danish public authorities and doctors who orchestrated the journeys and placements in Danish institutions had extensive decision-making powers, as their authority as experts remained largely unquestioned.

Samuelsen’s appeal to parents with disabled children to unite and act was therefore also meant as a wake-up call to Faroese society to thoroughly rethink their relationship to and responsibility for people with disabilities. As her article states, “children belong with their parents, and when they grow up, they should be allowed to make their own decision.” But there was also a reason for optimism: just a few weeks after Samuelsen’s newspaper appeal Javni, the first Faroese disability rights organization, was founded.

Run by parents with intellectually disabled children, Javni’s name was derived from a native, robust plant that was well-adapted to the harsh North Atlantic climate, as well as from the Faroese word for equality, javnaður. It was a fitting symbol for Javni’s ambitious goal, namely giving all people with cognitive disabilities the opportunity to live a self-determined life in their own country, and to bring back those who had been placed in Danish institutions.

“Up until now they have been sent away from their home country without even being asked”, Javni stated accusingly. This “great injustice”, as they called it, had to come to an end.

Overwhelmed Authorities, Medical Journeys and “Mapping” Disability

Throughout history, people with disabilities have been exposed to varying forms of marginalization, abuse and discrimination. To understand the extraordinary history of disabled Greenlanders and Faroese we have to go back to the mid-20th century, a time of radical and momentous change for both the countries.

The Faroe Islands, a Danish province since 1821, were granted political autonomy in 1948 as a self-governing country under the authority of the Danish realm. With this came a new responsibility for domestic policies – including disability issues. By that time, however, disability had already established itself as somewhat of a problem. The reason was a law from the late 19th century that allowed the “blind, deaf-mutes, idiots and the mentally ill” to apply for financial assistance from their respective municipalities, a right that was also continued in later legislation.

This assistance, the local authorities and doctors generally agreed, was best invested in placing disabled people in specialized Danish institutions, where they could receive professional care. The problem was:

most Faroese municipalities did not have the means to pay for the expensive sea voyages and years of all-around care. Instead, it was the Faroese families with disabled relatives themselves who bore the full burden of this situation.

Not knowing where else to turn to, both the local authorities, doctors and parents started to call out to the Danish state for help.

In the late 1950s, their pleas were finally answered. With the establishment of the State Service for the Intellectually Disabled (Statens Åndssvagesforsorg), Denmark assumed full responsibility for people with cognitive disabilities in the Faroe Islands, which included not only their accommodation in adequate facilities over in Denmark but also medical diagnosis and social counselling on site. In order to make this system more efficient, special consultants were employed who conducted home visits, assessing the mental and social capabilities of disabled children and the general living situation over a cup of coffee and a chat with the parents.

While rumours emerged that this was a ploy to “steal” Faroese children, many families saw these visits as a blessing, as this was often their very first contact with professional advice and support.

Many parents therefore gratefully agreed to send their children on the long journey to Denmark – where, it was hoped, they could benefit from a broad network of support that simply was not available on the Faroes.

In Greenland, the situation was exactly the opposite although at first glance it bears many similarities to its North Atlantic neighbour. A Danish colony since 1721, the largest island in the world only became a province (amt) and thus an equal part of Denmark in 1953. While the Faroese transition to self-government five years earlier had gone rather smoothly, the post-colonial period brought enormous upheavals into the lives of Greenlanders as Denmark, anxious to keep close ties to its former colony, began a veritable “modernization crusade”: small settlements transformed into towns with large building blocks and modern, Western lifestyles. Within a few years, Greenland was hardly recognizable.

Modernization also affected Greenlanders with disabilities. Similar to the Faroe Islands, Greenland did not have any infrastructure for rehabilitation, special education or disability housing to speak of, and many disabled people lived with their families or in elderly homes – even if they were still young.

But whereas disabled Faroese were mainly seen as a social and financial burden, disability in Greenland, especially cognitive and congenital ones, became perceived as a threat to public health.

With this danger in mind, Danish doctors from the late 1940s onward began to organize regular medical journeys along the Greenlandic coast in order to identify and “map” households with disabled residents. This was also mainly done by home visits, but the doctors also interviewed local authorities like priests or nurses and at times applied elaborate testing schemes to learn more about a disabled person’s behaviour, skills and cognitive abilities.

Communication was often difficult and many families did not understand the diagnosis of a disability or the implications of sending their children to care institutions in Denmark. The Danish view of these families and the local conditions in Greenland was rather condescending: “It is a great joy to see these children and young people thrive [in Denmark]”, as provincial physician Carl Clemmesen wrote in 1963, “after having seen them live in destitute conditions in Greenland.”

Changes and new beginnings

Soon, the negative effects of this practice came to light. While settling into the new environment of the institutions proved difficult for many of the disabled children from Greenland and the Faroes, it was not only the long distances that estranged them from their families and home countries.

By demanding assimilation to the Danish ways of living, they were also being deprived of their native language and culture. It did not take long for resistance against these “side-effects” to arise.

Javni, the Faroese parents’ organization, was one of the first and also one of the most outspoken on this issue. Only a few weeks after its setup in the spring of 1971, the young organization took initiative by imploring the Danish Minister of the Interior on his visit to the Faroe Islands to urge the Faroese authorities to open local facilities for people with disabilities. “They miss all contact with their families”, as Helena Samuelsen later wrote in an article in Tíðindablaðið 1974, “what would be better than for them to feel that they have a family to which they belong?”

This direct action eventually proved to be successful. In the course of the 1970s, the State Hospital in Tórshavn transformed a ward, the so-called Pensionatet, into rooms for 35 persons with intellectual disabilities. Some of them moved in from their family homes or their own apartments, others had just come back from Denmark. Javni was also proud to open its own facilities, among them several small-scale care homes, leisure centres and a brand new house at Eirargarður 14 and 16, close to downtown Tórshavn. More facilities for housing, education, training or leisure activities followed. Today, there are only about a dozen Faroese with intellectual and behavioural disabilities still in Denmark.

With the new facilities and public marketing campaigns, Javni became known throughout the islands in a flash. By the end of the 1970s, an article stated that the organization already had about 1.500 members – an enormous number considering that there were only 173 intellectually disabled Faroese in total, of whom about 70 lived in Danish institutions. Other disability organizations for the blind, deaf, mobility impaired or patients with multiple sclerosis could not quite match this success, although the public focus on disability certainly helped to bring all of them together in the cross-disability association Meginfelag fyri brekað í Føroyum (MBF) founded in 1981.

In Greenland, things developed at a similarly fast pace. The arctic island had gained Home Rule in 1979 after several years of political struggle and campaigns for indigenous rights. The tasks were challenging:

a new disability care system had to be created basically from scratch, parents demanded that their disabled children be returned to them, and above all, the influence of the Danish state had to be restricted.

Long long-simmering feelings of resentment towards Denmark that the affected families shared with the political autonomy movement transformed into a new narrative: that of a group of Greenlanders who had been deported, marginalized, and stripped of their cultural identity under the pretext of public health and modernization.

So what was to be done? Just like the Faroe Islands, Greenland prioritized the right to stay at home, meaning disabled Greenlanders had to be given the opportunity to stay in their native country and with or closer to their families. New integrative school classes, small-scale care homes, training facilities and counselling services opened in the larger towns.

In the report The North Atlantic Cooperation Project: Disabled People in the Local Community from 1990, a group of Danish social workers gives us a glimpse of daily life as disabled Greenlanders as they meet with Jens, a resident at a care home in Qaqortoq. But although the visitors are full of praise about how far Greenlandic disability care has come, they are also somewhat disappointed: the interior, they resume, looks almost exactly like that of an ordinary Danish apartment.

“Jens shows us his room and talks about his things, especially his souvenirs from Denmark, to honour the Danish guests. Jens has been in an institution in Denmark for 15 years. He came to Greenland a few years ago. He understands Greenlandic but speaks it poorly. He’d like to go back to Denmark, he confides to us in his room, but he says this only to be polite.”

The language barrier proved to be a major obstacle in reintegrating Greenlanders with disabilities into the Greenlandic society. Many had forgotten their native language or found it easier to communicate in Danish after years abroad. But staying at home was not a one-way process.

Greenlanders with disabilities were also invited to have a say in the political and social developments of their country, now that the Danish influence dwindled. And what could be better for this purpose than a festival?

In 1981, during the globally celebrated UN International Year of Disabled Persons, a group of disabled Greenlanders participated for the first time in the so-called aasivik, a political festival organized by the autonomous movement and various civil and cultural groups. Unlike the Faroe Islands, where disability was understood as an administrative matter, questions of nation-building and political self-determination were at the forefront of Greenlandic disability debates. Whereas Faroese authorities for decades had been reluctant to commit themselves to disability issues, many Greenlandic politicians were keen on making disability a priority – and thereby undo some of the damages inflicted by the journeys and placements in Danish institutions.

Even though many problems remain and persons with disabilities are still at times being accommodated in Denmark, these two examples from the remote North Atlantic illustrate the creative and inspirational powers that communities, self-advocacy organizations and engaged politicians can generate, and that disability has a rightful place right in political, societal and also postcolonial debates. To put it in the words of the Greenlandic Social Directorate in 1981:

“Persons with disabilities have the right to full participation in society’s life and development. It is our duty to give them the opportunity to make use of this right.”

Further readings:

- Derksen, Anna: ‘A Right to Live Where They’re at Home’: Identity, Nation-Building and the International Year of Disabled Persons 1981 in Greenland, in: Rethinking Disability Blog, 3 July 2017.

- Garðshorn Mikkelsen, Enna: Nedsendelser. Om nedsendelse af mennesker med udviklingshæmning fra Færøerne til Danmark i perioden 1897-1972. Handicaphistorisk Tidsskrift 34, 2015.

- Grønbæk Jensen, Stine and Marie Louise Knigge: Forvist til forsorg. Grønlænderemed handicap nedsendt til Danmark, Assens: Forlaget Udvikling, 2008.

- Hansen, Doris: Søgan um hini. 1895-1981, Tórshavn: Føroya Skúlabókagrunnur, 1996.

- Javni: Javnablaðið, 1973-. http://javni.fo/javnabladid.

Fagurferði hversdagsins

My Right to Exist

A flawless culture: Disability, ableism and erasure in the Nordics

Tannár - Buffalo skógvar, sjeikar og spik í '90inum

Read more about...