Miriam Petra

@mpawad

@miriampetra

images:

Eva Sigurðardóttir

@evasigurdar

@evasig__

evasigurdar.com

As an Icelandic woman whose paternal family originates in Egypt, I have for a long time been keeping track on the development of attitude and prejudice towards the Middle East in Icelandic society. Early on in my childhood, I remember the attitude being some sort of curiosity, influenced by Disney’s Aladdin, about camels and deserts. Magical and simple orientalism that made real people romanticised figures. The attitude became more negative after 9/11 which has only escalated since.

Statements on primitive people without culture, or with a bad culture.

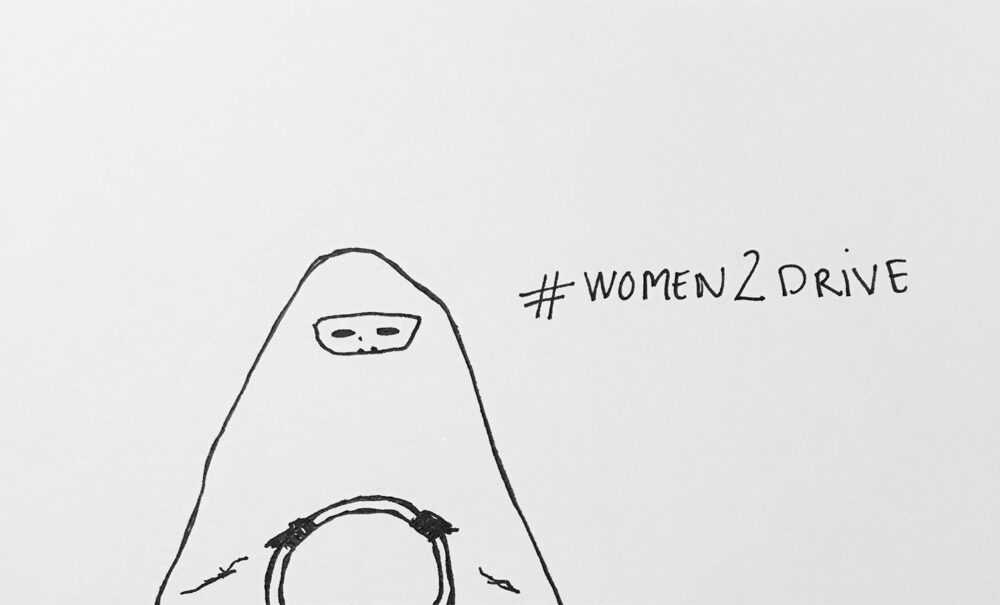

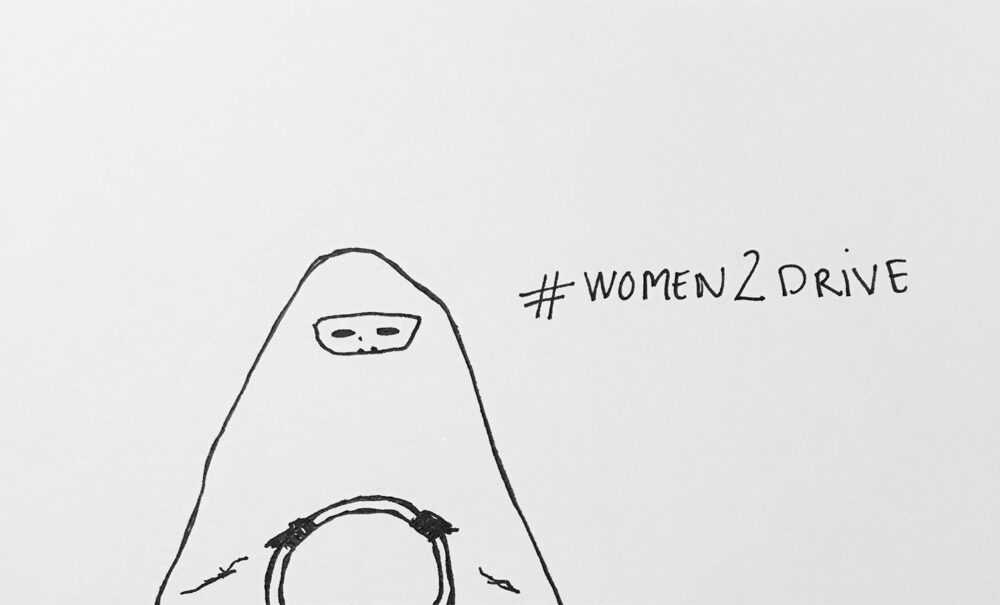

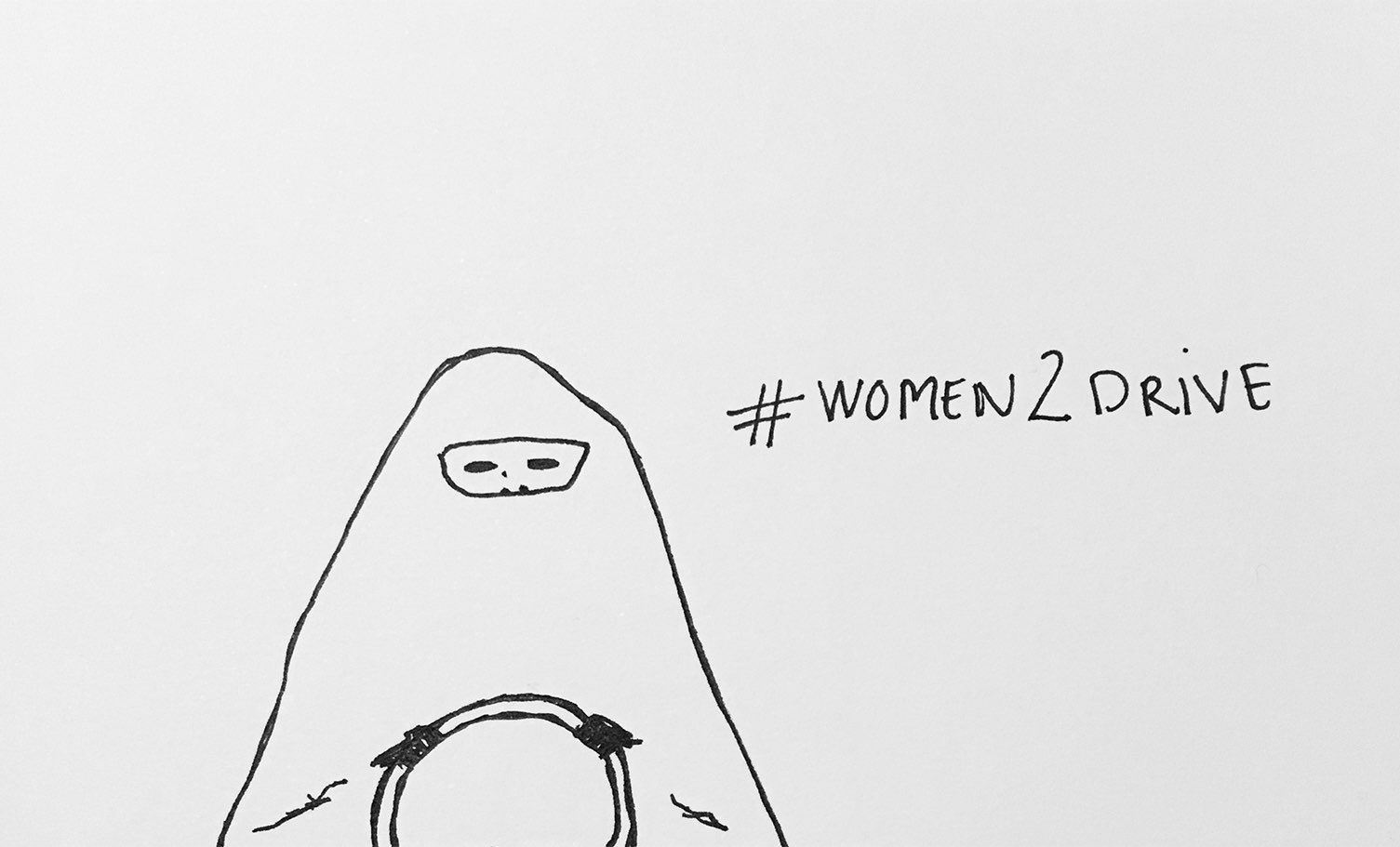

Terrorism, wars and people who do not assimilate to our societies. I have had to stand up against negative stereotypes of Middle Eastern women because stereotypes about them have been inflicted upon me. “But the women are subjugated, aren’t they?, “Oh, but then don’t you have to wear a headscarf when you go there?”, “Women aren’t really allowed to drive there, right?”, etc. Leading questions that are simply put forward to confirm the prejudice already in the mind of the one who asks.

In Western* countries, the Middle East and Islam have become synonymous with each other in the minds of many people, who expect a certain look, language and type of clothing. The stereotypes that are connected to these ideas are mainly negative and they are maintained by the media and popular culture. Islamophobia is abundant in online content, in the commentary sections of news websites and social media, but it also rears its ugly head in politics and in the words of politicians. Often the hateful commentary is not taken seriously, allowed to stand unchallenged and its seriousness doubted. Additionally, cultural traits from Middle Eastern countries are taken and mocked, put on display as the depiction of evil or primitivity. These stereotypes erase cultural diversity and by distorting people’s way of clothing, traditional outfits become a sort of costume anyone can play around in. That is, except those to whom the culture belongs. When people from that very culture dress in the same outfits, our societies often react negatively. Then it becomes undesirable.

Islamophobia also appears in the form of micro aggression and how negative stereotypes about Muslims influence people’s behaviour towards those who they assume are Muslims, or from the Middle East.

In the general understanding of our society, the Middle East is an area encompassing countries from the western tip of North Africa to South Eastern Asia, from Morocco to Pakistan. Imagine this area for a moment. Perhaps look at it on a map. It’s an immensely large geographical area with around 30 countries. In Europe there are 44 countries and most people would acknowledge there being a cultural difference between Finland and Spain for example, but somehow the Middle East remains in the minds of our societies as one immutable package. One package where the common denominator is often religion and the actual diversity of the countries is completely overlooked. At the same time all innovations and inventions introduced by Middle Eastern cultures throughout history are forgotten. The Middle East; Exotic, inferior and inherently different from the West.

These negative stereotypes do not distinguish between people’s lives either. Consequently, Middle Eastern women, or women who are Muslim, all fall into the same category. Generalisations about the women’s situation, their oppression or their inability to adapt to our societies are put forward, and often connotated with religion. In all discussions and popular culture, they appear as subjugated women living in societies or cohabitation with violent Middle Eastern men. International interference in Middle Eastern affairs has even been influenced by the need of saving these women from these men. Such attitudes could for example be seen in the US government’s rhetoric when justifying the invasion of Afghanistan. In the eyes of the West, these women are helpless, have no voice and are unable to choose their own destinies – women in danger that need to be saved.

One of the most distorted ways Middle Eastern women are brought to the limelight is the debate on Islamic clothing, most specifically the headscarf, in the West.

Their freedom to choose what they wear has been denied to them in some places – in the name of giving them freedom. Such freedom can become a hindrance when laws are put in place against the clothing in public spaces, an obstacle in their participation in Western societies. This fight against the headscarf has often been put forward under the flag of feminism but as the scholar Lila Abu-Lughod has rightly pointed out, feminism that tries to bring freedom to women by removing their freedom cannot be called feminism.

Feminists in the Middle East fight for the basic rights of women, against patriarchy and for better societies. They protest wars and fight for disarmament and peace. Some fight against gendered violence, other fight for women rights in the job market and others for LGBTQI+ rights just to mention a few. Recently I’ve for example seen appeals and social media campaigns arise in Egypt calling for increased action against sexual harassment and the realisation of the class injustice faced by many women in the country. Middle Eastern feminists have multiple focus fields – just like their counterparts elsewhere. Albeit – rarely do they fight for the ban of the headscarf. In the countries where women are forced to wear the headscarf, they fight for their rights to choose. Just like they want when they live in the West. The choice to decide for themselves.

Additionally, it is strange to speak about Middle Eastern women, or women who are Muslims, as one homogenous group as is often done. Their diversity is unlimited. Middle Eastern women can also be Christian, Jewish or atheists etc. and women who are Muslim can also be Icelandic, Malaysian and Ethiopian etc. The problem is, that when this diverse group is constantly being discussed as singular, we tend to not listen to their voices and assume their needs based off the negative stereotypes. This is why intersectional feminism is so important, not just feminism that works for the women in our own situation. Remembering that women around the world are diverse and solutions that might work for some don’t necessarily work for others. Factors like class, sexual orientation, skin colour and religion can all have an effect on women’s actual situation.

Middle Eastern culture isn’t homogenous, it’s a varied concoction of different religious and cultural influences in a region whose history spans thousands of years and covers a vast geographical area.

When this region is repeatedly taken and depicted as the manifestation of evil it is easy to become afraid of it. By that, people become afraid of the individuals that belong to, are related to or originate in that region. The fear becomes prejudice and suspiciousness which negatively affects individuals in our society. They become ostracised for their names, their language, their looks or their cultural identities and the marginalisation fosters suffering and inability to participate in society. This forms a vicious cycle that needs to be broken. Feminism is one of the greatest tools we as women have to break this cycle, but in order for that to be possible, feminism needs to be for all women – and this we can achieve when we listen to the voices of all women and give them a platform to speak.

COVID-19: The Virus and Social Status

My Right to Exist

Of Feminism in the Middle-East and Orientalism

Of Feminism in the Middle-East and Orientalism

Read more about...