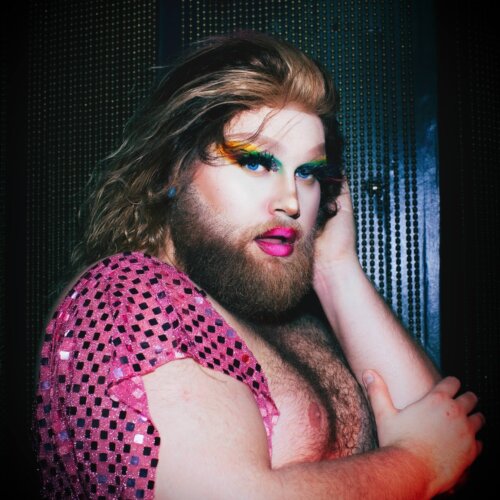

Bryn R. Frederiksmose

@brynhildrthedrag

dihdenmark.com

images

Ditte Marie Grønning

@billsanddreams

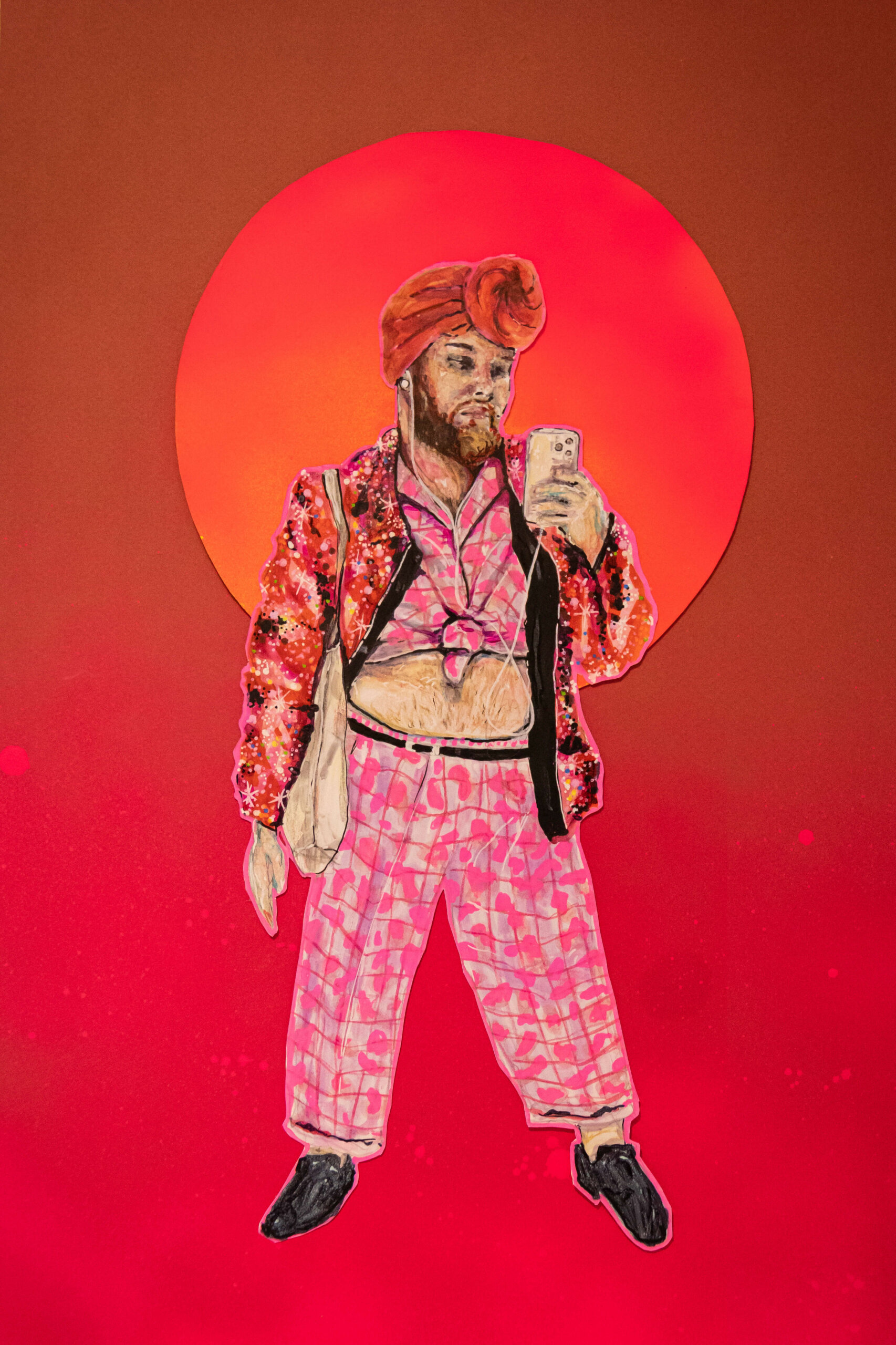

It wasn’t much past midnight, on a common Friday. My friend had gone with a random guy from the bar, and I had to walk home by myself. Dressed in a pastel blue pantsuit, with a scarf wrapped around my head, a shawl hanging from my shoulders, and a little lipstick, that was smushed on my lips from drinking all those glasses of wine earlier in the night. I had only just left the bar, when a few guys passed me and tauntingly yelled at me, and to hide, I tried to cover up within my shawl.

Across the street another group began to yell at me, and my shawl crept further up, covering my face in the shadows, while also pulling my mask up, covering my bearded chin. Now hidden from the prying eyes of the public, I continued to walk home. A taxi pulled up, and from the dark window came a voice asking me if a fine lady like me didn’t need a ride home, I didn’t have to pay; not with cash at least.

When we walk this earth, in any given society, there are certain unwritten rules, that we each are measured by.

We know these rules at heart, because when we see a man, we aren’t unsure that he’s a man, no need to see validation by showcasing of genitalia, but what exactly defines a man? Some would say it is genitalia, but not every man has the same genitalia. Heck, even cis men can loose their genitalia, and that doesn’t make them less of a man. Some would argue it’s a specific role within reproduction, but not every man is capable of making a person pregnant.

So what is it, that makes a man a man? Because we can walk down the street, and we know when we see a man coming toward us, and that is without being able to see either his chromosomes or his genitalia. This cis assumption, being able to walk within these social rules, gives a certain passability where people assume you’re cis. But what if you break this assumption? What if you clearly behave, move and act like a woman, but are built like a man?

I called my friend, with tears building in the corners of my eyes, and pleaded to the higher powers, how much I just wanted to pass. The burden of being othered was weighing on my shoulders, and I couldn’t do it no more.

How desperately I just wanted to pass, so I too could experience invisibility in a crowd, being desired the same way my girlfriends were desired, and to be able to breathe without my heart pounding in my chest.

My friend listened, and then she said, “even if you pass, the night is not your friend, and the desire from men doesn’t come without a price. The life of a woman isn’t the goal of safety that you seek, because the life of a woman isn’t safe.”

I’ve seen these social rules in action, because I move within them constantly. They are my playing field. It’s a constant dance with norms. Sometimes I do the steps of a man, putting on a performance to comply with the masses, and move from a to b without harm; it’s not who I am and the discomfort is great, but it’s an urgent possibility, as long as I don’t have to interact.

I’ve learned to quickly change my tone of voice, to regain what kind of male privilege left within me, in a situation that needs that to let me pass. Because truth is, even if I don’t essentially have cis assuming privilege, people still perceive me as a man, a strange effeminate man that is, but a man none the less. I can adapt; dance to the beat of society, but that rhythm gets tiring because it’s not the natural movements of my hips.

“The life of womanhood isn’t safe,” her words stuck with me for a while, as I continued my life, othered in my body by the values of society. Life goes on, and submitting to the dominators will only furthers their power, submitting to the gaze of the cis’es only further the idea that their way of living is correct; so I don’t comply or submit, I continue. But that doesn’t come without a price, because the lesson of fuckability was quickly expanded.

One night, on a drunken journey home, dressed in designer garments of pearls and silk, a man starts to record me on his phone. Mockingly and taunting he speaks to the telephone camera. My drunk courage reacts in the only way I know can be a useful defence against these men, and it’s sexualization. I use the submission in an act to regain power in the situation, but this time instead of creating discomfort in the violent man, his friend became angry and pulled a weapon on me.

In that moment I learned that there is a fine line between being viewed as an object valuable for sex, and an object without value that needs to be discarded. I was the latter.

It’s a weird sentence to write, because there truly is no gain in the dehumanization of being an object for the man’s sexual desire. But this lack of passability, took the worthiness of living out of my being, and left me without value in the male gaze, and his instinct of violence, didn’t go to sex, but instead it went to murder.

Being able to pass, being assumed as cis, is a difficult space to navigate in, and the values change depending on the eyes doing the scaling. It’s a method of safety, but how safe can it be when the options either are sexual violence or in the act of getting caught outside of cis-life, murder. The scale from which we are weighted is both upheld by our oppressor and our submission to his narrative.

Passability, en personlig essay

My Right to Exist

Trans: Becoming Myself

Harm reduction and the right of individuals to self-determination — Frú Ragnheiður

Read more about...